Книгу нельзя скачать файлом, но можно читать в нашем приложении или онлайн на сайте.

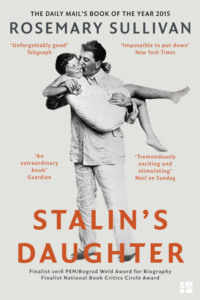

Читать книгу: «Stalin’s Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana Alliluyeva», страница 4

Nadya’s second year at the Industrial Academy, 1929, was the Year of the Great Turn and the forced collectivization of the peasantry into kolkhozy, or collective farms. The process was brutal. In order to root out private enterprise, village markets were shut down and livestock was confiscated. Kulaks, or prosperous peasants (owning one cow could constitute prosperity), were deported. Under this policy, known as dekulakization, peasants, “treated like livestock . . . often died in transit because of cold, starvation, beatings in the convoys, and other miseries.”19 By the year of Nadya’s death, 1932, the infamous Gulag (forced-labor camps) held “more than a quarter of a million people,” and 1.3 million, “mainly deported kulaks,” were living as “special settlers.”20

In 1932 and 1933, famine raged in the Ukraine. Stalin and his ministers were shipping grain supplies abroad to pay for smelters and tractors in order to sustain the rapid pace of industrialization. Though the Ukraine Politburo begged for emergency relief, no assistance came. Millions died. In 1932, a number of Nadya’s fellow students at the Industrial Academy were arrested for speaking out about the famine. Nadya, too, was rumored to oppose “collectivisation and its immorality.” Critical of Stalin, she secretly sympathized with Nikolai Bukharin and the right-wing opposition.21 Stalin commanded Nadya to stay away from the Academy for two months.22

In the early days, Nadya attempted to exert some influence. When Stalin was vacationing alone in Sochi in September 1929, Nadya wrote him a careful letter, reporting that the Party was exploding over a dispute at Pravda; an article had been published without first being cleared by the Party hierarchy. Though many had seen the article, everyone was laying the blame on her friend Leonid Kovalev, and demanding his dismissal. In a long letter with the simple salutation “Dear Josef,” she wrote:

Don’t be angry with me, but seriously I felt pain for Kovalev, for I know the colossal work that he has done in the paper. . . . To dismiss Kovalev . . . is simply monstrous. . . . Kovalev looks like a dead man. . . . I know that you detest my interference, but still I believe that you should look into this absolutely unjust outcome. . . . I cannot be indifferent about the fate of such a good worker and comrade of mine. . . . Good-bye, now, I kiss you tenderly. Please, answer me.23

Stalin wrote back four days later: “Tatka! Got your letter regarding Kovalev. . . . I believe you are right. . . . Obviously, in Kovalev they have found a scapegoat. I will do all I can, if it is not too late. . . . I kiss my Tatka many, many, many times. Yours, Josef.”24 Stalin did act on Nadya’s request and wrote to Sergo Ordzhonikidze, in charge of adjudicating cases of disobedience to Party policies, to say that scapegoating Kovalev was “a very cheap but wrong and unbolshevik method of correcting one’s faults. . . . Kovalev . . . IN NO CIRCUMSTANCES WOULD EVER let one line about Leningrad be printed, had it not been silently or directly approved, by somebody at the bureau.”25 Kovalev was eventually dismissed from Pravda—not as an “enemy of the people” but rather as “a straying son of the Party.”26

Nadya wrote back rather pathetically: “I am very glad that in Kovalev’s matter you have shown me your trust” and went on to report that the Academy was very friendly. “The academic achievements are judged according to rules: ‘kulak,’ the ‘center,’ the ‘poor one.’ We laugh a lot daily about that. I am already characterized as a right-wing,” a strange admission to make to Stalin who would soon destroy the so-called right-wing opposition.27

There were clearly mounting tensions between Nadya and Stalin. She wrote in the summer of 1930, “This summer I did not feel that you might be pleased with a postponing of my departure, quite the contrary. The last summer I did feel that, but not now. . . . Answer me, if not too displeased by my letter, or rather, as you wish.”28 He wrote back to say that her reproaches were “unjust.”29 In October she wrote, “No news from you. . . . Maybe hunting quails absorbed you too much, or just too lazy to write.”30 Stalin responded with irony: “Lately you have begun to praise me. What does that mean? Good or bad news?”31 Nadya’s letters to Stalin in Sochi often contained reports of the hunger in Moscow, the long lines for food, the lack of fuel, the disrepair of the city. “Moscow looks better now, but in some places like a woman who covered with powder her defects, especially after rains, when the paint runs in stripes. . . . One wishes so that these shortcomings would one day leave our lives, and people would then feel wonderful and work remarkably well.”32

By the time of her suicide, it is possible that Nadya was not schizophrenic but rather disillusioned with her husband’s revolutionary politics. The night of her death, she refused to raise her glass in Stalin’s toast to “the destruction of enemies of the state.”

Nadya’s friend Irina Gogua, who had known her since their shared childhood in Georgia, when the Alliluyev children, having no bathroom in their own apartment, had come for weekly Saturday baths at her house, remembered how Nadya behaved in Stalin’s presence.

[Nadya] understood a lot. When I returned [to Moscow], I understood that her friends were arrested somewhere in Siberia. She . . . demanded to see their case. So she understood a lot. . . . In the presence of Joseph she resembled a fakir, who performs in the circus barefoot walking over broken glass. With a smile for the audience and with a terrifying intensity in her eyes. This is what she was like in the presence of Joseph, because she never knew what was coming next—what kind of explosion—he was a real cad. The only creature who softened him was Svetlana.

Gogua was not surprised when she heard the gossip that Nadya had committed suicide. Though the truth about her suicide was immediately suppressed, Gogua claimed that it was known among the security organizations. She added an interesting detail to her story. “Nadezhda had very perfect features and very beautiful features. But here is the paradox. The fact that she was beautiful was observed only after her death. . . . In the presence of Joseph, she was always like a fakir—always internally tense.”33

As recently as 2011, Alexander Alliluyev, the son of Nadya’s brother Pavel, offered a convincing detail in the puzzle of Nadya’s suicide with a piece of the story that came to him from his parents.34

Pavel was at work when he heard the news that his sister had committed suicide. He immediately phoned his wife, Zhenya. He told her to stay where she was; he’d be right home. When he arrived, he asked where she had hidden the packet of papers that Nadya had given them. “In the linen,” Zhenya replied. “Get them,” he told her.

Nadya had been planning to leave Stalin. She intended to go to Leningrad and had even asked Sergei Kirov, head of the Communist Party organization there, about getting a job in the city. In the packet of papers she left with her brother was supposedly a parting letter for him and his wife.

Zhenya kept the existence of the letter secret for two decades and spoke to her son, Alexander, of its contents only in 1954, after Stalin’s death. She told her son that Nadya had written that she “could not live with Stalin anymore. You take him for someone else. But he is a two-faced Janus. He will step over everybody in the world, including you.” Alexander commented, “We all came to know what kind of a person Comrade Stalin was, but at the time, only Nadya knew about this.”

Zhenya asked Pavel what they should do with the letter, and he replied, “Destroy it.” The destruction of the letter and documents, of course, makes it impossible to verify the story, as is the case with so many stories about the inscrutable Stalin.

As an adult, Svetlana always believed that Nadya committed suicide because she had concluded there was no way out. How could one hide from Stalin? Svetlana’s nanny later told her of overhearing Nadya’s conversation with a female friend just days before she committed suicide. Nadya said that “everything bored her, she was sick of everything, and nothing made her happy.” “What about the children?” the friend asked incredulously. “Everything, even the children,” Nadya replied.35 Such boredom was a sign of profound depression, but it was a painful account for her daughter to hear. Her mother had been “too bored.” Svetlana’s responses to her mother would always swing, unresolved, between sentimental idealizations and bitter anger.

Svetlana could not remember how or when she was told of her mother’s death or even who told her. She remembered the formal resting in state that began at 2:30 on November 9. The news of Nadya’s death had been shocking, and hundreds of thousands of Muscovites wanted to say good-bye to her, even though many were hearing her name for the first time. Stalin kept his family life very private.

Nadya’s open coffin rested in the assembly hall at the GUM; a huge building with atria, it housed government offices as well as the GUM department store. Irina Gogua remembered that the lines of people outside were so long that some of the uninitiated public wondered what the stores were giving away.36 Svetlana remembered that Zina, the wife of Uncle Sergo Ordzhonikidze, took her hand and led her up to the coffin, expecting her to kiss her mother’s cold face and say good-bye. Instead she screamed and drew back.37 That image of her mother in her coffin seared itself in her mind, never to be dislodged. She was rushed from the hall.

There are several versions of Stalin’s behavior at the ceremony. In one, he sobbed, and Vasili held his hand and said, “Don’t cry, Papa.” In another, Molotov, Polina’s husband, always recalled the image of Stalin approaching the coffin with tears running down his cheeks. “And he said so sadly, ‘I didn’t save her.’ I heard that and remembered it: ‘I didn’t save her.’”38 In Svetlana’s retelling, Stalin approached the casket and, suddenly incensed, shoved it, saying, “She went away as an enemy.”39 He abruptly turned his back on the body and left. Had Svetlana herself heard this? The anecdote sounds like retrospective invective and does not seem like the observation of a six-year-old in hysterics. Perhaps this was someone else’s story.

A cortege of marching soldiers accompanied the coffin carried on a draped gun carriage covered in flowers. Vasili walked with Stalin beside Nadya’s coffin in the procession to the Novodevichy Cemetery. Svetlana was not present.

Svetlana believed her father never visited her mother’s grave. “Not even once. He couldn’t. He thought my mother had left him as his personal enemy.” Yet there were stories from Stalin’s drivers of secret nocturnal visits to Nadya’s grave site, especially during the coming war.40

Mourners walk alongside Nadya’s coffin during the procession to Novodevichy Cemetery in November 1932. Vasili is the small boy in the front row. Svetlana was not present.

(Meryle Secrest Collection, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University)

Pravda reported Nadya’s death in a perfunctory manner, without explanation. Her suicide was a state secret, though everyone in the apparat knew about it. The children, along with the public, were told another story: Nadya had died of peritonitis after an attack of appendicitis.

It would be ten years before Svetlana learned the truth about her mother’s suicide. Though this might seem astounding, it is entirely credible. The terror that Stalin had begun to spread around him particularly infected those closest to him. Who would dare tell Stalin’s daughter that her mother had committed suicide? Many would be shot simply for knowing the truth. It soon became “bad form” even to mention Nadya’s name.

Stalin was clearly shocked by Nadya’s death, but he got over it. He wrote to his mother:

MARCH 24, 1934

Greetings Mother dear,

I got the jam, the ginger and the chukhcheli [Georgian candy]. The children are very pleased and send you their thanks. I am well, so don’t worry about me. I can endure my destiny. I don’t know whether or not you need money. I’m sending you 500 rubles just in case. . . .

Keep well dear Mother and keep your spirits up. A kiss.

Your son,

Soso

P.S. The children bow to you. After Nadya’s death, my private life has been very hard, but a strong man must always be valiant.41

But for very young children the scars caused by a parent’s death are profound, in part because death is not something their young minds can grasp; they understand only abandonment. Svetlana’s adopted brother, Artyom Sergeev, remembered Svetlana’s seventh birthday party, four months after her mother’s death. Everyone brought birthday presents. Still not sure what death meant, Svetlana asked, “What did Mommy send me from Germany?”42 But she was afraid to sleep alone in the dark.

A childhood friend, seven-year-old Marfa Peshkova, granddaughter of the famous writer Maxim Gorky, remembered visiting Svetlana after Nadya’s death. Svetlana was playing with her dolls. There were scraps of black fabric all over the floor. She was trying to dress her dolls in the black fabric and told Marfa, “It’s Mommy’s dress. Mommy died and I want my dolls to be wearing Mommy’s dress.”43

Chapter 3

The Hostess and the Peasant

Stalin with Vasili and an eight-year-old Svetlana.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

Svetlana always divided her life into two parts: before and after her mother’s death, when her world changed utterly. Her father immediately decided to move out of the Poteshny Palace, where the shade of Nadya hovered in every corner. Nikolai Bukharin offered to swap his ground-floor apartment in the Kremlin Senate, also known as the Yellow Palace, where Lenin had once had his private residence. Stalin accepted.

The apartment was long and narrow with vaulted ceilings and darkened rooms and had once served as an office. Svetlana hated it. The only familiar object was a photograph of Nadya at Zubalovo, wearing her beautifully embroidered shawl; Stalin had had the picture enlarged and hung in the dining room over the elaborately carved sideboard. Svetlana filled her bedroom with mementos of her mother. Stalin’s office was on the floor above, and the Politburo met in the same building.

Svetlana’s home was now full of vigilant strangers. It was run on a military model with a staff of agents of the OGPU (the secret police) who were called “service personnel” rather than servants. Svetlana felt they treated everyone but her father as nonexistent. She was sure her mother would never have allowed such an invasion, but Stalin obviously thought the quasi-military regimen of the household fitting. His children were not to be spoiled. No luxuries, no indulgences. He probably also thought the security was necessary. Enemies were about.

Even Svetlana’s beloved Zubalovo had altered. When she and Vasili returned there after their mother’s death, she was devastated to find the tree house they called “Robinson Crusoe” dismantled, and the swings gone.1 For security reasons, the sandy roads had been covered with ugly black asphalt, and the beautiful lilacs and cherry bushes had been dug up. While the extended family still frequented Zubalovo on weekends and Grandpa Sergei lived there most of the time, Stalin seldom visited the dacha again.

Grandmother Olga continued to live in a small apartment in another building in the Kremlin. With its Caucasian rugs, its takhta covered with embroidered cushions, and the old chest holding photographs, Olga’s apartment was the only welcoming space in this strange new world. When Svetlana visited, she would find her grandmother raging at the new regimen. She called the “state employees” a waste of public money. The staff retorted that she was “a fussy old freak.”2

Svetlana’s maternal grandmother, Olga Alliluyeva, in an undated photograph.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

It was soon clear that Stalin had no intention of living in the Kremlin. Shortly after Nadya’s death, he had his favorite architect, Miron Merzhanov,3 design him a new dacha in the village of Volynskoye in the district of Kuntsevo, about fifteen miles outside Moscow. He called it Blizhniaia, the “near dacha.” Stalin was said to have chosen this name for its useful vagueness in telephone conversations that might be overheard by enemies. The sixteen-room dacha, painted camouflage green, sat in the center of a forest. To approach it one had to drive down a narrow asphalt road and pass through a sixteen-foot-high fence with searchlights mounted, within which was a second barrier of barbed wire. Svetlana detested her father’s new dacha. She said that the dacha and the Kremlin apartment continued to surface in her nightmares for decades.

By 1934, Stalin had moved to his dacha in Kuntsevo. Most evenings, he came down the stairs of the Yellow Palace to dine at the Kremlin apartment with his children. With him would be members of his inner circle, all men. Svetlana would rush to the dining room. Her father would seat her on his right. As the men talked business, she would stare up at the framed photograph of her mother over the sideboard. Her father would turn to her and ask about her school marks and sign her school daybook. This, at least, was her memory of family dinners. Though she never mentions her brother, presumably Vasili was also there and equally silent. At the end of the meal, Stalin would dismiss his children and continue his discussions with his Politburo members into the small hours of the morning. Then he would head out to Kuntsevo, where he slept. Sometimes he would come upstairs in his overcoat to give his sleeping daughter a good-night kiss.

Stalin’s departure was an elaborate ritual. There would be three identical cars with tinted blue windows waiting outside. Stalin would pick one, climb in, and move off in a cordon of guards, taking a different car and a different route each night. The traffic on the Arbat and Minskoye highways was stopped in four directions. He always waited until the last minute to tell his personal secretary, Alexander Poskrebyshev, or his bodyguard, Nikolai Vlasik, that he intended to leave for his dacha.4

Life at the Kuntsevo dacha also had a military tone, with commandants and bodyguards. Two cooks, a charwoman, chauffeurs, watchmen, gardeners, and the women who waited on Stalin’s table all worked in shifts. They, too, were employees of the OGPU. The commandants and bodyguards, in particular, were high functionaries rewarded for their services with Party privileges: good apartments, dachas, and government cars. Valentina Istomina—everyone, including Svetlana, affectionately called her Valechka—soon joined the household as Stalin’s personal housekeeper and stayed with him for eighteen years. According to Molotov, there were many unconfirmed rumors that she was Stalin’s bed companion.5

Though the nanny Alexandra Andreevna was permitted to stay with Svetlana in the Kremlin apartment, a new governess, Lidia Georgiyevna, arrived in 1933. Svetlana disliked this governess immediately for reprimanding her nanny: “Remember your place, Comrade.” The seven-year-old Svetlana shouted back, “Don’t you dare insult my nanny.”6

With her mother gone, Svetlana’s devastation was palpable, and she directed her neediness toward her father. She spent August 1933 with her nanny in Sochi. There she wrote to her father, who was in Moscow:

AUGUST 5, 1933

Hello my dear Papochka [Daddy],

How are you living and how is your health? I received your letter and I am happy that you allowed me to stay here and wait for you. I was worried that I would leave for Moscow and you would come to Sochi and I would not see you again. Dear Papochka, when you come you will not recognize me. I got really tanned. Every night I hear the howling of the coyotes. I wait for you in Sochi.

I kiss you.

Svetanka7

It had been nine months since her mother’s death. A child, afraid of the dark, listens to the coyotes howling in the woods, worried that her father will disappear. She was seven years old. She waited. This unappeasable emotional hunger would return without warning to sabotage Svetlana throughout her life.

Stalin seems to have been somewhat aware of his young daughter’s psychological needs. Candide Charkviani, a visiting writer and politician whom Stalin admired and promoted, described in his memoirs how shocked he was to discover that “Stalin, someone who absolutely lacked sentimentalism, expressed such untypical gentleness towards his daughter. ‘My little Hostess,’ Stalin would say, and seat Svetlana on his lap and give her kisses. ‘Since she lost her mother I have kept telling her that she is a homemaker,’ Stalin told us.”8

Stalin had loving diminutives for Svetlana. She was his “little butterfly,” “little fly,” “little sparrow.” He developed a game for her, which they continued to play until she was sixteen. Whenever she asked him for something, he would say, “Why are you only asking? Give an order, and I’ll see to it right away.”9 He called her his hostess and told her he was her secretary; she was in charge. He would descend from his office on the upper floor of the Yellow Palace and head down the hall, shouting, “Hostess!”

But this was still Stalin. He also invented an imaginary friend for Svetlana called Lyolka. She was Svetlana’s double, a little girl who was perfect. Her father might say he’d just seen Lyolka and she’d done something marvelous, which Svetanka (the affectionate diminutive Stalin used) should imitate. Or he might draw a picture of Lyolka doing this or that. Secretly, Svetlana hated Lyolka.

When he was staying at his dacha in Sochi, Stalin would write his daughter letters in the big block script of a child, signing them Little Papa:

To My Hostess Svetanka:

You don’t write to your little papa. I think you’ve forgotten him. How is your health? You’re not sick, are you? What are you up to? Have you seen Lyolka? How are your dolls? I thought I’d be getting an order from you soon, but no. Too bad. You’re hurting your little papa’s feelings. Never mind. I kiss you. I am waiting to hear from you.

Little Papa 10

Stalin called himself Secretary No. 1. Svetlana would write short notes to Secretary No. 1 with her orders, and pin these with tacks on the wall near the telephone above his desk. Amusingly, she also sent missives to all the other “little secretaries” in the Kremlin. Government ministers, such as Lazar Kaganovich and Vyacheslav Molotov, had no choice but to play the game.

Svetlana would order her Secretary No. 1 to take her to the theater, to ride the new subway, or to visit the Zubalovo dacha.

OCTOBER 21, 1934

To Comrade J. V. Stalin.

Secretary No. 1

Order No. 4

I order you to take me with you.

Signed: Svetanka, the Hostess

Seal

Signed: Secretary No. 1

I submit. J. Stalin 11

Stalin always spent several months each fall working alone at his southern dacha in Sochi; Svetlana would be left in her nanny’s hands. She would write her father loving letters, but one can hear the solicitude and tentativeness in her tone:

SEPTEMBER 15, 1933

Hello my dear Papochka,

How do you live and how is your health? I arrived well except that my Nanny got really sick on the road. But everything is well now. Papochka, don’t miss me but get better and rest and I will try to study excellently for your happiness. . . .

I kiss you deeply.

Your Svetanka 12

Stalin’s letters could be affectionate and teasing:

APRIL 18, 1935

Hello Little Hostess!

I’m sending you pomegranates, tangerines and some candied fruit. Eat and enjoy them, my little Hostess! I’m not sending any to Vasya [Vasili’s nickname] because he’s still doing badly at school and feeds me nothing but promises. Tell him I don’t believe promises made in words and that I’ll believe Vasya only when he really starts to study, even if his marks are only “good.” I report to you, Comrade Hostess, that I was in Tiflis for one day. I was at my mother’s and I gave her regards from you and Vasya. She is well, more or less, and she gives both of you a big kiss. Well, that’s all right now. I give you a kiss. I’ll see you soon.13

He signed his letters: “From Svetanka-Hostess’s wretched Secretary, the poor peasant J. Stalin.”

There were others who remembered the little “hostess.” Nikita Khrushchev managed to stay in Stalin’s favor after Nadya’s death. He recalled Svetlana as a lovely little girl who was “always dressed smartly in a Ukrainian skirt and an embroidered blouse” and, with her red hair and freckles, looked like “a dressed-up doll.”

Stalin would say: “Well, hostess, entertain the guests,” and she would run out into the kitchen. Stalin explained: “Whenever she gets angry with me, she always says, ‘I’m going out to the kitchen and complain about you to the cook.’ I always plead with her, ‘Spare me! If you complain to the cook, it will be all over with me!’” Then Svetlanka [sic] would say firmly that she would tell on her papa if he ever did anything wrong again.14

The game of the Hostess and the Peasant might have seemed charming, but it had a dark side. Khrushchev claimed that he felt pity for little Svetlana “as I would feel for an orphan. Stalin himself was brutish and inattentive. . . . [Stalin] loved her, but . . . his was the tenderness of a cat for a mouse.”

A British journalist, Eileen Bigland, recalled meeting Svetlana in 1936 when she was a “lumpy schoolgirl” of ten. “Her father adored her. He loved listening to her exploits in the Park of Rest and Culture. He patted her delightedly when she played ‘The Blue Bells of Scotland’ on the piano. He was a rough and tumble father to her, a pincher and a teaser—like a bear with a cub—and you felt at any minute that he might cuff her like a bear. She was a jolly little girl.”15

The Kremlin contained a small cinema on the site of what had once been the Winter Garden, linked by passageways to the Kremlin Senate. After the usual two-hour dinner, which ended at nine p.m., Svetlana would beg her father to let her stay up. He would feign displeasure and then laugh. “You show us how to get there, Hostess. Without you to guide us we’d never find it.”16

It was thrilling for the child to race ahead of the procession through the passageways and out across the grounds of the deserted Kremlin. Behind her followed her father, his cronies, the security guards, and at a distance, the slow-moving armored car that now always accompanied the vozhd. The movies would end at two a.m. When the last film was over, Svetlana would race back through the empty grounds, leaving the men behind to continue their discussions.

Stalin viewed all new Soviet films in the Kremlin before they were released to the public, so the ones Svetlana watched were often Russian: Chapayev, Circus, Volga-Volga. But Stalin loved American Westerns and particularly Charlie Chaplin films, which would send him into fits of laughter—with the exception of Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, which was banned.17 She would always think back nostalgically to these times: “Those are the years that left me with the memory that he loved me and tried to be a father to me and bring me up as best he knew how. All this collapsed when the war came.”18

After her mother’s death, as Svetlana put it, her father became the “final, unquestioned authority for me in everything.”19 None was more brilliant at psychological manipulation than Stalin, the “poor peasant” controlling his little “hostess.” Svetlana would spend a lifetime trying to rip off the mask of compliance that she had invented for her father. She would often succeed, spectacularly, only to find the mask slipping back over her face. A paradox was forming: a child who could order around the most powerful members of the Politburo as her secretaries, but also a dreadfully lonely little girl who learned to behave.

Though it is often said that the family disintegrated after Nadya’s death, the family members refute this. All of them—Grandfather Sergei and Grandmother Olga, Uncle Pavel and Aunt Zhenya, Aunt Anna and Uncle Stanislav, Uncle Alyosha and Aunt Maria Svanidze—continued to visit. For the next two or three years, the Alliluyevs and Svanidzes remained close to Stalin. There were shared trips in the summer to Sochi, and the New Year and birthdays were celebrated at Stalin’s Kuntsevo dacha. According to Svetlana’s cousin Alexander Alliluyev, the family was fragile but united, still absorbing the shock of Nadya’s suicide, all of the relatives asking themselves: “Why did we not see it coming?” Alexander’s father, Pavel, felt particularly guilty about giving his sister that small gun.20

From left: Vasili, future Supreme Soviet chairman Andrei Zhdanov, Svetlana, Stalin, and Svetlana’s half brother Yakov at Stalin’s dacha in Sochi, c. 1934.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

It is even possible that Stalin was keeping up some semblance of family ties. When Svetlana was nine, he arranged for her, Yakov, and Vasili to visit his mother, Keke, in Tiflis. It was 1935, two years before Keke’s death. Though the palace in Tiflis was grand, she continued to live like a peasant in a ground-floor room. The visit was not a success. Keke terrified Svetlana. Sitting up in her black iron cot surrounded by old women dressed in black who looked like crows, she tried to speak to Svetlana in Georgian. Only Yakov spoke Georgian. Svetlana took the candies her grandmother offered her and retreated outside as soon as she could.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Начислим

+38

Покупайте книги и получайте бонусы в Литрес, Читай-городе и Буквоеде.

Участвовать в бонусной программе