Книгу нельзя скачать файлом, но можно читать в нашем приложении или онлайн на сайте.

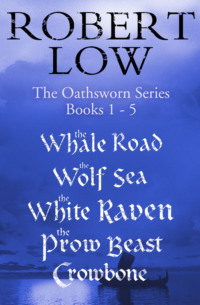

Читать книгу: «The Oathsworn Series Books 1 to 5», страница 2

They drank, too, great amounts of ale, the foam spilling down their beards while they joked and made riddles. Steinthor, it was clear, fancied himself as a skald and made verses on the bear-slaying, while the others thumped benches or threw insults, depending on how good his kennings were.

And they raised horns to me, Orm the Bear Slayer, with my father, new-found and grinning with pride as if he had won a fine horse, leading the praise-toasts. But I saw that Gunnar Raudi was hunched and quiet on his ale bench, watching.

That night, as the men fell to talking quiet and lazy as smoke drifting from the hearthfire, I fell asleep and dreamed of the white bear and how it had circled the walls and then fallen silent.

I turned to say to Freydis that her walls were well built; I was sure that we had weathered it, that the bear was gone. I was smiling when the roof caved in. The turf roof. Two massive paws swiped and the earth and snow tumbled in and then, with a crash like Thor’s thrown hammer, the bear followed: an avalanche of white; a great rumbling roar of triumph.

Numbed, I pissed myself then and there. The bear landed in a heap, shook itself like a dog, scattering earth and snow and clods, and then got on all fours.

It was a cliff of fur, a rank, wet-smelling shriek of a thing that swung a snake neck with a horror of a head this way and that, one eye red in the firelight, the other an old, black socket. On that same side, the lips had been straked off, leaving the yellow tusk teeth exposed in a grim grin. The drool of its hunger spilled, thick and viscous.

It saw us; smelled the ponies, didn’t know which to go for first. That was when I ran for it and so decided the skein of all our lives.

The white bear whirled at my movement – the speed of it, and it so huge! It saw me at the door, scrabbling for the bar. I heard it – felt it – roar with the fetid breath of a dragon; I frantically tore the bar off and dragged the door open.

I heard it crash, half-turned to look over my shoulder as I scrambled out. It had risen on hind legs and lumbered forward. Too tall for the roof, its great head had smacked a joist – cracked it – and tumbled it down into the fire.

I swear I saw it glare its one eye at me as it shrieked; I also saw Freydis calmly stand, pick up the old spear and ram it at the beast’s ravening mouth. Not good enough. Not nearly a good enough spell, after all. The spear smashed teeth on the already ruined side, snapped off and left the head and part of the haft inside.

The bear lashed out, one casual swipe that sent Freydis flying backwards in a spray of blood and bone. I saw her head part company from her body.

I ran stumbling through the snow. I ran like a nithing thrall. If there had been a baby in my way I would have tossed it over one shoulder, hoping to tempt the beast into a snack and giving me more time to get away …

I woke in Gudleif’s hall, to a sour-milk smear of a morning and the sick shame of remembering, but everyone was too busy to notice, for we were leaving Bjornshafen.

Leaving my only home and never returning, I realised. Leaving with a shipload of complete strangers, hard men for the sailing and raiding and, worse yet, a father I hardly knew. A father who had, at the very least, watched his brother’s head part company from the rest of him and not even shrugged over it.

I could not breathe for the terror of it. Bjornshafen was where I had learned what every child learns: the wind, the wave and war. I had run the meadows and the hayfields, stolen gulls’ eggs from the black cliffs, sailed the little faering and crewed the hafskip with Bjarni and Gunnar Raudi and others. I had even gone down to Skiringssal once, the year Bluetooth buried his father Old Gorm and became King of the Danes.

I knew the place, from the skerry offshore where the surf creamed on black rocks, to the screaming laughter of the terns. I fell asleep at night rocked in the creaking beams as the wind shuddered the turf of the roof, and felt warm and safe as the fire danced the shadows of the looms like huge spiders’ webs.

Here Caomh had taught me to read Latin because no one knew runes well enough – when I could be pinned down to follow his hen-scratching in the sand. Here was where I had learned of horses, since Gudleif made his name breeding fighting stallions.

And all that was changed in an eyeblink.

Einar took some barrels of meat and meal and ale, as part of the ‘bloodprice’ for the bear, then left instructions to bury Freydis and drag the bear corpse in and flay the pelt from it. Gudleif’s sons could keep that and the skull and teeth, all valuable trade items, worth more than the barrels taken.

Whether it was worth their father was another matter, I thought, gathering what little I had: a purse, an eating knife, an iron cloak brooch, my clothes and a linen cloak. And Bjarni’s sword. I had forgotten to ask about it, it had never been mentioned, so I just kept it.

The sea was grey slate, capped white. Picking through the knots of dulse and rippled, snow-scattered sand, the Oathsworn humped their sea-chests down to the Fjord Elk, plunging into the icy sea with whoops, boots round their necks. White clouds in a clear blue sky and a sun like a brass orb; even the weather tried to hold me to the place.

Behind me, Helga scraped sheepskins to soften them, watching, for life went on, it seemed, even though Gudleif was dead. Caomh, too, watched, waiting by Gudleif’s head – until we were safely over the horizon, I was thinking, and he could give it a White Christ burial.

I said as much to Gunnar Raudi as he passed me by and he grunted, ‘Gudleif won’t thank him for it. Gudleif belonged to Odin, pate to heel, all his life.’

He turned back to me then, bowed under the weight of his own sea-chest and looked at me from under his red brows. ‘Watch Einar, boy. He believes you are touched by the gods. This white bear, he thinks, was sent by Odin.’

It was something that I had thought myself and said so.

Gunnar chuckled. ‘Not for you, boy. For Einar. He believes it was all done to bring him here, bring him to you, that you have something to do with his saga.’ He hefted the chest more comfortably on his shoulder. ‘Learn, but don’t trust him. Or any of them.’

‘Not even my father? Or you?’ I answered, half-mocking.

He looked at me with his summer-sea eyes. ‘You can always trust your father, boy.’

And he splashed on to the Fjord Elk, hailing those on board to help haul his sea-chest up, his hair flying, streaked grey-white and red like bracken in snow. As I stood under the great straked serpent side of the ship, it loomed, large as my life and just as glowering. I felt … everything.

Excited and afraid, cold and burning feverishly. Was this what it meant to be a man, this … uncertainty?

‘Move yerself, boy – or be left with the gulls.’

I caught my father’s face scowling over the side, then it was gone and Geir Bagnose leaned over, chuckling, to help me up with my rough pack, lashed with my only spare belt. ‘Welcome to the Fjord Elk,’ he laughed.

TWO

The voyages of the Northmen are legendary, I know. Even the sailors of the Great City, Constantinople, with their many-banked ships and engines that throw Greek Fire, stand in awe of them. Hardly surprising, since those Greeks never lose sight of land and those impressively huge vessels they have will go keel over mast in anything rougher than a mild chop.

We, on the other hand, travel the whale road, where the sea is black or glass-green and can rear over you like a fighting stallion, all roar and threat and creaming mane, to come crashing down like a cliff. No bird flies here. Land is a memory.

That’s what we boast of, at least. The truth is always different, like a Greek Christ ikon veiled on feast days. But if anyone boasts of spitting in Thor’s eye, standing in the prow, roaring defiance at the waves and laughing the while, you will know him for the liar he is.

A long journey is always being wet to the skin and the wind bites harder as a result and your clothes are heavy as mail and chafe you until you have sores where the cloth rubs on wrist and neck.

It’s huddled in the dark, bundled in a wet cloak, feeling the sodden squash every time you turn. It’s cold, wet mutton if you are lucky, salt stockfish if you are not and, on truly long voyages, drinking water that has to be strained through your linen cloak to get rid of the worst of the floating things and no food at all.

There wasn’t even a storm of any serious intent on this, my first true faring; just a mild pitch of wave and a good wind, so that the company had time to erect deck covers of spare sail, like small tents, to give some shelter, mainly to the animals.

Einar huddled under his own awning, aft. The oars were stacked inboard and the only one with serious work was my father.

And my task? A sheep was mine. I had to care for it, keep it warm, stop it panicking. At night I slept, my fingers entwined in the rough, wet wool while the mirr washed us. In the morning, I woke with spray and rain washing down the deck. If I moved, I squelched.

The first week we never saw land at all, heading south and west from Norway. My sad ewe bawled with hunger.

Then we hit the narrow stretch of water which had Wessex on one side and Valland, the Northmen lands of the Franks on the other. We made landfall a few times – but never on the Wessex side. Not since Alfred’s day.

Even then we kept to the solitary inlets and lit fires only when we were sure there was no one for miles. Nowhere was safe for a boatload of armed men from the Norway viks.

We sailed north then, up past Man, where there was much argument for putting in at Thingvollur and getting properly dry and fed. But Einar argued against it, saying that people would ask too many questions and someone would talk and the news would get to Strathclyde before we did.

Grumbling, the men hauled the Elk further north, into the wind and the white-tressed sea.

Three more days passed, during which no one spoke much more than grunts and even the sheep had no strength left to bleat. For the most part, we huddled in solitary misery, enduring.

I dreamed of Freydis often, and always the same vision: her receiving me on the morning I arrived. She wore a blue linen dress with embroidery round the throat and hem, her brooches had strange animal heads and between them was a string of amber beads. She made no movement save for the rhythmic stroking of the growling cat.

‘From the pack, I take it you have come from Gudleif,’ she said to me. ‘Since he would only miss this journey if he were sick or injured, I presume that to be the case. Who are you?’

‘Orm,’ I replied. ‘Ruriksson. Gudleif fosters me.’

‘Which is it?’

‘Sorry?’

‘Sick or injured.’

‘He has sent for his sons.’

‘Ah.’ She was silent for a moment. Then: ‘So were you his favourite?’

My laugh was bitter enough for her to realise. ‘I doubt that, mistress. Why else would he send me through the snow to the hall of a—’ I stopped before the words were out, but she caught that, too, and chuckled.

‘A what? Witch? Old crone?’

‘I meant nothing by it, mistress. But I was sent away and I think he hoped I would die.’

‘I doubt that,’ she said crisply, rising so that the cat sprang off her lap and then arched in a great, shivering bow of ecstasy before stalking off. ‘Call me Freydis, not mistress,’ she went on, smoothing her front. ‘And ponder this, young man. Ask yourself why in … how old are you?’

I told her and she smiled gently. ‘In fifteen years, you and I have never met, though we are but a day apart and Gudleif came every year. Ask that, Orm Ruriksson. Take your time. The snow will not melt in a hurry.’

‘He sent me to die in the snow,’ I said bitterly and she shrugged.

‘But you did not. Perhaps your wyrd is different.’

Then the hall changed, to the one I had sat in under her bloodsoaked sealskin cloak, with the roof caved in. Yet still she sat on her bench, the cat somehow back on her lap.

‘I am sorry,’ I said and she nodded her head off her shoulders, so that it tumbled into her lap, sending the cat leaping up with a yowl …

I woke to the cold and wet, wondering if she was fetch-haunting me. Wondering, too, what had happened to the cat.

Then Pinleg yelled out from the prow, where he was coiling walrus-hide ropes. When he had our attention, he pointed and we all squinted into the pearl-light of the winter sky.

‘There,’ shouted Illugi Godi, pointing with his staff. A solitary gull wheeled, staggered in the wind, dipped, swooped and then was gone.

My father was already busy, with his tally stick and his peculiar devices. I never mastered them, even after he had explained them to me.

I knew that he had two stones, like grinding wheels, free-mounted. One pointed at the north star and the other was fixed to point at the sun. That way, my father knew the latitude, by seeing the angle of the sun stone. He could calculate longitude by using that and what he called his own time, marked on his tally stick.

I never understood any of it – but at the end of four days I knew why Einar valued Rurik the shipmaster, because we found the land at the point where we were supposed to find it, then my father, leaning over the side, watching the water, announced that a suitable inlet lay no more than a mile away, one where we could get ashore and sort ourselves out.

He read water like a hunter reads tracks. He could see changes in colour where, to anyone else, it was just featureless water.

The mood had changed and everyone was suddenly alert and busy. The sail came down, a great sodden mass of wool which had to be sweatily flaked into a squelching mass and stowed on the spar.

The oars came out, that watch of rowers took their sea-chest benches and Valgard Skafhogg, the shipwright, took a shield and beat time on it with a pine-tarred rope’s end until the rowers had the rhythm and away we went.

Pinleg swayed past me, smiling broadly and clapping a round helmet on his head. He had a boarding axe in one hand and a wild light in his eye. It was hard for me to realise that Pinleg was older than me by ten years, since he was scrawny and no bigger than I was.

I wondered how such a runt – his leg was permanently crippled, from birth I learned, so that he walked with a sailor’s roll even on dry land – had ended up in the Oathsworn. I learned, soon enough, and was glad I had never asked him.

‘I’d leave the sheep, Bear Killer,’ he chuckled. ‘Grab your weapons and get ready.’

‘Are we fighting?’ I asked, suddenly alarmed. It occurred to me that I had no idea where we were, or who the enemy would be. ‘Where are we?’

Pinleg just grinned his mad grin. Nearby, Ulf-Agar, small, dark as a black dwarf and with an expression as sullen, said, ‘Who cares? Just get ready, Bear Killer. Pretend they are lots of bears. That will help.’

I glanced at him, knowing he was taunting me and not knowing why.

Ulf-Agar hefted his two weapons – he scorned a shield – and curled a lip. ‘Stay behind Pinleg if you are worried. Killing men is different from bears, I will grant you. Not everyone is cut out for it.’

I knew I had been insulted; I felt my face flame. I realised, with a sick lurch, that Ulf-Agar was probably deadly with his axe and seax, but a slight is a slight …

A hand clasped my shoulder, gentle but firm. Big-bellied Illugi Godi, with his neat beard and quiet voice, spoke softly: ‘Well said, Ulf-Agar. And not everyone can kill a white bear in a stand-up fight. Perhaps, when you do, you will share your joy with Rurik’s son?’

Ulf-Agar offered him a twisted smile and said nothing, suddenly interested in the notching on his seax. Then: ‘I have a spear, Bear Killer,’ he remarked, with an edge-sharp smile. ‘Since you drove your own up into the head of that beast, you may want to borrow it.’

I turned away without replying. Ulf-Agar wanted the tale to be a lie, for it was a task Baldur would have been hard put to manage, let alone a scrawny man/boy. And the nightmare of it hag-rode me to a shivering, soaked waking most nights, which I am sure Ulf-Agar had not been slow to notice.

The nightmare was always one of those where you are running from some horror and yet you cannot get your legs working fast enough – which is what happened when I spilled out of that doorway, leaving Freydis to her wyrd. I was sobbing and panting and struggling in the snow. I fell, got up and fell again.

My knee hit something, hard enough to make me gasp. The wood sled. The bear lumbered forward, spraying snow like a ship under full sail. I had Bjarni’s sword still, was surprised to find it locked in my hand.

I picked up the sled awkwardly, stumbled a few steps and half fell, half hurled myself on it. It slid a few feet, then stopped. I kicked furiously and it moved. I heard the bear grunting and puffing through the snow close behind me.

I kicked again and the sled slithered forward, picked up a little speed, then a little more. I felt the hissing wind of a swiped paw, a fine mist of blood on my ears and neck from its ruined mouth as it roared … then I was away, hurtling down the hill, the bear galloping clumsily after, bawling rage and frustration.

There was a confusion of snow spray and darkness, a howl from behind me, then the sled tilted, bucked and I flew off, spilling over and over in the snow. I came up spitting and dazed. Something dark, a huge boulder, hurtled past me, still spraying snow and blood, rolling down the hill towards the trees. There was a splintering crash and a single grunt.

And silence.

Shaking woke me and I stared up at Illugi, ashamed that I had fallen asleep at all when everything else was bustle and purpose.

‘We are in Strathclyde,’ he said. ‘We have a task inland. Einar will explain it all later, but best get ready for now.’

‘Strathclyde,’ muttered Pinleg, shoving past us. ‘No easy raiding here.’

The landing was almost a disappointment for me. With my sword in one hand and a borrowed shield in the other – Illugi Godi’s, with Odin’s raven on it – I waited in the belly of the Fjord Elk as it snaked smoothly into the bow of land.

Shingle beach stretched to a fringe of trees and, beyond, rose to red-brackened hills, studded with trees, warped as old crones. There were rocks, too, which I took for sheep for a moment and was glad I had not called out my foolishness.

Since nothing moved, everyone relaxed. Except for Valgard Skafhogg, who bellowed at my father as the keel ground on shingle stones, calling him a ship-wrecking son of Loki’s arse. My father bellowed right back that if Valgard was any good as a shipwright, then a few stones wouldn’t sink us and, from what he had heard, Valgard couldn’t trim his beard. Which was a good joke on his nickname, Skafhogg, which means Trimmer.

But it was almost good-natured as we splashed ashore, to a smell of bracken and grass that almost made me weep.

It was bitter cold and you could taste the snow. The sail was dragged out, unfurled and draped over a frame – not as a shelter, since it was sodden; we only wanted it to dry out a little. Then we’d put it back, for when we returned to this place, we’d be in a hurry to get away from it.

Lookouts were posted and fires were lit for us to dry clothes and, above all, get warm. I staked out the sheep, as I had before, on a long line for her to crop what she could of the frozen grass and brown-edged fern and bracken.

She had little time to enjoy it and I was almost sorry when she was up-ended, gralloched and spitted. Brought all that way in damp misery, simply to be the hero-meal before the Oathsworn went into fight: I identified strongly with that wether.

I wondered about the fires, since the wood was wet and smoked and you could see it for miles, but Einar didn’t seem bothered. Now that we were so close, he had tallied that warmth and a full belly was worth the chance of discovery.

My father, now free of any duties, since he had done his part, crossed to where I sat shivering by the fire and trying not to wear my drying cloak until the rest of me had lost some water.

‘You need some spare clothing. Maybe we’ll get some soon.’

I glanced sourly at him. ‘A seer now, are you? If so, tell us where we are raiding.’

He shrugged. ‘Someplace inland.’ He stroked his stubbled chin thoughtfully and added, ‘Strathclyde’s not a place to raid these days, never mind inland. Still, Brondolf is paying good silver for it, so we do.’

‘Brondolf?’ I asked, helping him as he started to erect a shelter from our cloaks, making a frame of withies.

‘Brondolf Lambisson, richest of the Birka merchants. He hires the Oathsworn of Einar the Black this year. And last, come to think of it.’

‘To do what?’

My father tied cloak corners together, blowing on his fingers to warm them. The sky was sliding into dour night and it would soon be colder yet. The fires already looked flower-bright comforts in the growing dark.

‘He leads the other merchants of Birka. The town was a great trading centre, but it is failing. The silver is drying up and the harbour silting. Brondolf seems to think he has found an answer. He and his tame Christ godi, Martin from Hammaburg. They keep sending us out to get the strangest things.’ He broke off at a thought and chuckled, uneasy as all Northmen were with the concept. ‘Who knows what he is doing? Perhaps he is working some spell or other.’

I knew of Birka only from old Arnbjorn, the trader who came to Bjornshafen twice a year with cloth for Halldis and good hoes and axes for Gudleif. Birka, tucked up in an island far east into the Baltic off the coast of Sweden. Birka, where all the trade routes met.

‘Is that where you have been all these years, then: searching out dead men’s eyes and toadspit?’ I demanded.

He made a warding sign. ‘Shut that up for a start, boy. Less mention of … such things ... is always safer. And, no, I wasn’t always doing that. For a time I thought to have a white bear safely tucked away, the price of a small farm.’

‘Is that what you told my mother? Or did she die waiting for your return?’

He seemed to droop a little, then looked at me from under his hair – it was thinning, I noticed – one eye closed. ‘Go fetch some bracken for bedding. We can dry it at the fires beforehand.’ Then he sighed. ‘Your mother died giving you birth, boy. A fine woman, Gudrid, but too narrow in the hip. At the time I had a farm, not far from Gudleif as it happens. I had twenty head of sheep and a few cows. I was doing well enough.’

He stopped, staring at nothing. ‘After she died, there didn’t seem much point in it. So I sold it to a man from the next valley, who wanted it for his son and his wife. Most of the money went to Gudleif, when I made him fostri. Some he was to keep and the rest was for you when you came of age.’

Surprised by all this, I could only gape. I had known she died … but the knowledge that I had killed my mother was vicious. I felt clubbed by Thor’s own hammer. Her and Freydis. They’d do better to call me Woman Killer.

He mistook my look, which was the mark of us, father and son. Neither knew the other and constantly misread the signs.

‘Yes, that was the reason Gudleif’s head went,’ he said. ‘I thought him my friend – my brother – but Loki whispered in his ear and he used the money on his own sons. I think he hoped I would die and that would be an end of it.’ He paused and shook his head sadly. ‘He had reason to think that, I suppose. I was never a good husband, or a good father. Always trying to live the old way – but too much is changing. Even the gods are under siege. But when he fell ill and sent for his own sons, thinking he was dying, Gunnar Raudi sent for me and Gudleif knew it was all up with him.’

‘So he did try to kill me in the snow,’ I said. ‘I was never sure.’

Rurik shrugged and scratched. ‘Nor he, I think. If Gudleif had wanted you dead, there were easier ways, though Gunnar Raudi wouldn’t have gone with it. A sound blade is Gunnar and you can trust him.’

He broke off, looked sideways at me and scrubbed his head in a gesture I was coming to know well, one that revealed his uncertainty. Then he chuckled. ‘Perhaps, after all, Gudleif sent you to Freydis to have her make you a man.’ His look was sly and he laughed aloud when my face flamed.

Yes, Freydis had done that, popped me on her the way Gudleif used to put me on his horses when I could barely walk. He made you wrap your hands in the mane and hang on until you learned to ride or fell off. If you fell off, he would pop you on again.

When I thought of it, Freydis was much the same. Blurry with the mead I had brought, greasy-chinned with lamb, she had caught me by the arm and dragged me close, stroking my hair and answered the riddle she had set me and I had failed to understand.

‘I can manage everything, have done since my Thorgrim, curse his bad luck, fell down the mountain,’ she said dreamily. ‘The year after that, Gudleif arrived at my door. I can cart dung and spread it on the hayfields, herd cows, herd horses, milk, make bread, sew, weave … everything. But Gudleif provided the thing that was missing.’

I couldn’t move, could scarcely breathe, though I was hard as a bar of sword-iron and too dry-mouthed to speak.

‘Now he cannot and he sends you,’ she went on and rolled me on her.

‘Come. I will teach you what you were sent here to learn.’

‘Good was Freydis,’ my father said, himself bleared with fond memories. ‘Gudleif swore she was a witch and had made him return every year and stay until he could hardly crawl on the back of a horse to ride off the mountain. If Halldis knew, she kept quiet over it. She was rich as good earth, was Freydis … but lonely. All she wanted was a good man.’

I looked at him and he grinned. ‘Aye, me too. And Gunnar, probably. In fact, if there was a man who hadn’t ploughed that field, then he lived in the next valley but one and was too lame to travel.’

I said nothing. I wanted to tell him of Freydis and her spell and how she had killed the bear with a spear while I ran … A vision, again, of that head, lazily turning, spraying fat drops of blood in an arc. Had she smiled?

When I eventually crawled to the side of it, the bear was already dead, the haft of the spear driven clear up and out the top of its skull by the impact with a tree. It had hit the slope and over-run its own feet. It was still a huge cliff of snow, frightening even when still. I saw, numbly, that the hair under its chin was soft and nearly pure white. One sprawled paw, big as my head, was shaking gently.

I sat down, trembling. Freydis’s spell had worked. Perhaps the price had been her own death. Perhaps she knew. I blubbered and there was no one reason for it. For her. For the knowledge of my own fear. For my father and Gudleif and the whole mess.

Eventually, I was shaking too much to cry. I was half-naked in the cold and had to get back to the hall. The hall and Freydis. I didn’t want to go back there at all, where her fetch might be, waiting accusingly. But I would freeze here.

The bear shifted and I scrambled away. A final kick? I had seen chickens and sheep do that with their throats cut through. I didn’t trust this bear. I remembered Freydis and my fear, took a deep breath, crossed to it and drove Bjarni’s sword into where I thought the heart would be, deep inside the mass of that white cliff.

It was a good sword and I was strong, made stronger yet through fear. It went in so smoothly I practically fell forward on the rank, wet fur; there was no great gout of blood, just a slow welling of fat drops. The sword was in nearly to the cross guard and I couldn’t get it out.

Eventually, shivering uncontrollably, I gave up and slogged back up the slope, through the door and into the ruin of the hall, wrapped myself in her cloak for the warmth and waited, sinking into the cold, where Bagnose and Steinthor found me.

It was a bad enough memory to have rattling round your thought-cage. Now, to add to all that, there was a new horror: a vision of me, like a small bear, clawing another Freydis from the inside out, charging out from between her legs in a glory of gore and challenge. I couldn’t see the face of the woman, my mother, though.

I shook my head, near to weeping, and knew it was for me more than anyone and wanted to back away from that, ashamed.

My father gripped my forearm wordlessly. Probably he thought I was mourning Freydis, or my mother. Truth to tell, I was not even sure which myself.

More alone than ever, I picked my way through the camp, where men chaffered and yacked and busied themselves, out into the trees to get bracken, aware of his eyes following me, aware that he was as much a stranger as all the others.

I wondered if he had taken his brother’s head, or if Einar had. What must it feel like, to have to kill your brother? Even just to watch him die?

Yet they were still men, these Oathsworn. Grim as whetstone, cold as a storm sea, but men for all that.

Most had wives and families – in Gotland, or further east – and went back to them now and then. Pinleg had a woman and two little ones whom he sent money back to by traders he could trust. Skapti Halftroll had more than one woman in more than one place, but he spent all his money on finery. Ketil Crow was outlawed from somewhere in Norway and had no one but the Oathsworn.

There were others, though, who were men apart. Sigtrygg was one, for he called himself Valknut and wore that rune symbol on his shield, three triangles known as the Knot of the Fallen. It meant he had bound his soul to Odin, would die at the god’s command and even the swaggerers walked soft around him.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Начислим

+52

Покупайте книги и получайте бонусы в Литрес, Читай-городе и Буквоеде.

Участвовать в бонусной программе