Книгу нельзя скачать файлом, но можно читать в нашем приложении или онлайн на сайте.

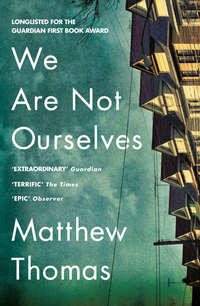

Читать книгу: «We Are Not Ourselves», страница 10

The memory of wealth haunted the nearby garden apartment buildings. She imagined gaunt bachelors presiding over dwindling fortunes, long lines coming to a silent end. There were remnants of the way it had been, like Barricini’s Chocolates and Jahn’s, but stepping into them only reminded her how few of the old places were left.

She knew it was possible to see the changes as part of what made the city great, an image of what was to come, the necessary cycle of immigration, but only if you weren’t the one being displaced. Maybe even then you could, if you were a saint. She had no desire to be a saint, not if it meant she’d have to blunt the edge of her anger at these people. It certainly wasn’t saintliness that led her to attempt to get past her resentment at the break-in that occurred a couple of years back, while they were on a cruise in the Bahamas. Rather, it was a desire to continue living in the neighborhood without boiling over into outright vitriol whenever she stepped into the grocery store, where anyone she laid eyes on, worker or customer, unless they looked respectable, could have been one of the offenders. She had returned from that cruise to find her jewelry box rifled through and her drawers turned inside out. Luckily, she’d long ago overridden Ed and spent the money to rent a safe deposit box at Manufacturers Hanover, where she stored Ed’s LeCoultre watch and her mother’s embattled engagement ring. All the bonds were in the box as well. She took a certain satisfaction in thinking of how little the thieves had made off with; for once it seemed an advantage that Ed had never been the sort to buy necklaces and bracelets for her birthday or their anniversary. The degenerates had pinched Ed’s stereo, that was true, but he’d needed a new one for years, and this was an excuse for her to buy one for him. She was angry too at the Orlandos, who’d been home at the time. She couldn’t imagine how they hadn’t heard anything, or done anything if they’d heard. What kept her awake some nights, though, fantasizing about revenge, was the fact that they’d taken Mr. Kehoe’s clarinet from the bedroom closet. What could they possibly have wanted with a clarinet? How valuable could such a thing have been on the secondhand market? There was no way they were keeping it for themselves, because the swine wouldn’t know what to do with such a delicate instrument. She pictured them back in their sty of an apartment, surveying their loot, sniffing it, looking at the clarinet’s pieces in stupefaction and dropping them into a garbage can.

She couldn’t blame everything on the latest waves of immigration. Her immediate neighbors had been there longer than she had and both had fallen on tough times. Both houses used to look respectable, if a little dull, with dingy lace curtains in the windows and bleached paint on the trim, but now a rusted-out car sat on blocks in the Palumbos’ backyard, next to a rain-filled drum, and Gene Cooney’s house was under permanent construction, with ugly scaffolding marring the facade and a garden box full of crabgrass and construction debris. Gene stalked the perimeter all day with an edgy intensity, wearing a tool belt around his waist. Wild rumors had sprung up about him and his family, spread by newer residents. He was said to be an IRA arms smuggler lying low. There were whispers about his daughter, who wore short skirts and fishnet stockings and kept nocturnal hours. Eileen knew the truth: he’d gone off the rails after his wife had been killed on Northern Boulevard by a hit-and-run driver, and his daughter wasn’t a prostitute but a girl who had fallen victim to the fashions of the Hispanics she’d grown up around—though one could be forgiven for confusing some of them with hookers.

When she’d first moved onto the block, the garden boxes in front of the houses were lush with flowers in bloom and respectable attempts at horticulture, but many had since returned to the wild, with giant weeds poking up over their walls. She was committed to making hers an oasis against decay, although she hadn’t inherited her father’s sympathy with all manner of vegetable life. Angelo had helped her keep things alive, and she’d picked up a bit of knowledge working alongside him, but ever since his third heart attack had killed him a few years back, she was constantly buying new plants to replace the ones that wilted in the middle of the night.

She overspent on furniture. She had the rugs cleaned and the walls painted every two years. She’d found a beautiful crystal chandelier on sale on the Bowery. The house wasn’t fancy, but it had a certain luster. The one thing she couldn’t escape was the sound of the Orlandos’ footsteps above her. The fact that she owned the whole building didn’t make it any more pleasant to hear them.

Ed was seated at the table as she fixed the tea. His back was to her, possessed of that solidity that so delighted her the first time she put her arms around him. Now she wanted to pound on it. He was hunched over and rubbing his temples. She put a hand on his shoulder and he flinched at her touch. She thought, Who the hell does he think I am?

She considered flinging herself on him before he could get the headphones plugged in. She thought of ripping the plug out once he’d settled into his pillow and filling the room with sound, screaming over the music the invectives she’d held in. But she didn’t do that. She sat in the armchair and read a book until she headed to bed.

She wondered whether she was being hard on her husband. He had, after all, more than earned a rest after teaching for so many years. She hadn’t heard anything from Connell yet about it, and she expected that the boy, who was becoming a more sullen presence in the house as he slunk into adolescence, would be oblivious enough to his father’s new routines to allow her to conclude that it was all in her head.

Connell noticed, though. “So what’s with all the record listening?” he asked one night, snapping his gum in that insouciant way that usually annoyed her. Now she saw that the attitude gave him the courage to speak.

Ed looked up but didn’t respond.

“What’s up with the headphones?” he asked again, stepping closer to his father.

Given the strange way Ed had been behaving lately, she thought he might fly into a rage, but he simply took the headphones off.

“I’m listening to opera.”

“You listen to it all the time now.”

“I decided I didn’t want to die not having heard all these masterpieces. Verdi. Rossini. Puccini.”

“Who’s dying? You’ve got plenty of time.”

“There’s no time like the present,” Ed said.

“You don’t have to use those,” Connell said, pointing to the headphones.

“I don’t want to disturb anyone.”

“You don’t think you’re disturbing anyone this way?”

Another night, when she picked him up from track practice, Connell asked her in the car if his father was unhappy.

“I wouldn’t say that,” she said. “I think he’s quite happy.”

“He always says, ‘You have to decide in life. You deliberate awhile, you think of all the possibilities on both sides, and then you make a decision and stick to it.’”

She’d never heard this particular line of reasoning from Ed. This must’ve been one of those things he and the boy talked about when she wasn’t around. She could almost feel her ears pricking up.

“Like with girls. He says, ‘When you’re getting married, you make a decision and that’s it. Things aren’t always perfect, but you work at them. The important thing is that you decided.’”

Her stomach tightened.

“But what I don’t get is, if it’s such a chore, if you’re talking about having to stick to it because you decided it, why do people do it in the first place?”

“They do it because they’re in love,” she said defensively. “Your father and I were in love. Are in love.”

“I know,” he said.

It occurred to her that perhaps he didn’t know. Overt affection had always been uncomfortable for her, but in front of the boy it felt impossible. Ed used to squeeze and kiss her when Connell was a baby, but she would wriggle out of it. Certainly she didn’t reach for him herself, but he knew when they married that he’d have to take the lead. She wasn’t like the women a few years younger who wore miniskirts. What she offered instead was the negotiated submission of her fierce independence. She was different in bed with him than she was anywhere else, but this wasn’t something her son could have any idea about.

“Your father is happy,” she said. “He’s just getting older, is all. You’ll understand someday. The same exact thing will happen to you.”

It didn’t feel like the best explanation, but it must’ve been good enough, because the boy was silent for the rest of the ride.

16

His father was always on the couch now, but that morning he came to Connell’s room and told him he wanted to take him to the batting cages. They drove to the usual place, off the Grand Central Parkway, in back of a mini-mall.

Connell picked out the least dinged-up bat from the rack and tried to find a helmet that fit. His father came back from the concession stand with a handful of coins for the machines. Connell headed for the machine labeled Very Fast. He put the sweaty, smelly helmet on and pulled his batting glove onto his right hand. He took his position in the left-handed batter’s box and dropped the coin in. The light came on on the machine, and then nothing happened for a while, until a ball shot out and thumped against the rubber backstop. Connell watched another one pass and wondered if he was going to be able to hit any of them. They were easily over eighty miles an hour, though they weren’t the ninety miles an hour they were presented as.

The next pitch came and Connell timed his swing a little too late and the ball smacked behind him with a fearsome thwack. The next pitch he foul-tipped, and the one after that he hit a tiny grounder on, and then the next one he sent on a line drive right back at the machine. It would have been a sure out, but it was nice to hit it with authority. His father let out a cheer behind him, and Connell promptly overswung on the next pitch, caught the handle on the ball and felt a stinging, ringing sensation in his hands and hopped in place, then swung through the next pitch entirely.

“Settle down, son,” his father said. “You can hit these. Find the rhythm.”

The next pitch, which he foul-tipped, was the last, and he stopped and put the bat between his legs and adjusted his batting glove. There wasn’t a line forming behind him, so he could take his time. Balls pinged off bats in nearby cages and banged off piping or died in the nets. His father had his hands on the netting and was leaning against it.

“You ready?”

“Yeah.”

“Go get ’em.”

He put a coin in and took his stance. The first pitch buzzed past him and slammed into the backstop.

“Eye on the ball,” his father said. “Watch it into the catcher’s mitt. Watch this one. Don’t swing.”

He watched it zoom by.

“Now time it. It’s coming again just like that. Same spot. This is all timing.”

He took a big hack and fouled it off. He was getting tired quickly.

“Shorten your swing,” his father said. “Just try to make contact.”

He took another cut, a less vicious one, more controlled, and drilled it into what would have been the outfield. He did it again with the next pitch, and the one after that. The ball coming off the bat sounded like a melon getting crushed. The whole place smelled like burning rubber.

When the coins ran out, he held the bat out to his father. “You want to get in here?”

“No,” his father said. “You have fun.”

“I don’t mind.”

“I don’t think I could hit a single pitch.”

“Sure you could. You’re selling yourself short.”

“My best days are behind me,” his father said.

“Why don’t you take a few hacks? Come on, Dad. Just one coin.”

“Fine,” his father said. “But you can’t laugh at me when I look like a scarecrow in there.”

His father came into the cage and took the helmet from him. He took the bat, refused the batting glove. He was in a plaid, button-down shirt and jeans that fit him snugly, and Connell thought that he actually did look a little like a scarecrow. His glasses stuck out from the helmet like laboratory goggles. Connell stepped out of the cage and positioned himself where his father had been standing. His father dropped the coin in and took his place in the batter’s box, the lefty side, Connell’s side.

The first pitch slammed into the backstop. The next one did as well. His father had the bat on his shoulder. The next pitch came crashing in too.

“Aren’t you going to swing?”

“I’m getting the timing,” his father said.

The next pitch landed with a thud, and the following one went a little high and came at Connell. His father didn’t offer at any of them.

“You have to swing sometime,” Connell said. “Only three left.”

“I’m watching the ball into the glove,” he said. “I’m waiting for my pitch.”

“Two left.”

“Okay,” his father said.

“Dad. You can’t just stand there.”

The last pitch came and his father took a vicious cut at it. The ball shot off like cannon fire and the bat came around to rest on his father’s back in textbook form, Splendid Splinter form. The ball would have kept rising if it hadn’t been arrested by the distant net, which it sank into at an impressive depth.

“Wow!”

“Not bad,” his father said. “I think I’m going to quit while I’m ahead.”

Connell went in and took the helmet and bat from his father, who looked tired, as if he’d been swinging for half an hour. He dropped the coin in and found the spot in the batter’s box. His father’s hit must have freed his confidence up, because he made solid contact on all but one of his swings, and then he put another coin in and started attacking the ball, crushing line drives.

“Attaboy,” his father said.

He hit until he was tired, and they drove to the diner they liked to go to after the cages. Connell ordered a cheeseburger and his father ordered a tuna melt. They shared a chocolate shake. Connell drained his half and his father handed him his own to drink.

“That’s okay, Dad.”

“You drink it,” his father said.

The food came and his father didn’t really eat. Instead he seemed to be looking interestedly at Connell.

“What’s up?” Connell asked.

“I used to love to watch you eat. I still do, I guess.”

“Why?”

“When you were a baby, maybe two years old, you used to put a handful of food in your mouth and push it in with your palm. Like this.” His father put his hand up to his mouth to show him. ‘More meatballs!’ you used to say. Your face would be covered in sauce. ‘More meatballs.’ You had this determined expression, like nothing was more important in the world.” He was chuckling. “And you ate fast! And a lot. You used to ask for more. ‘All gone!’ you said. I used to love to watch you eat. I guess it was instinct. I knew you would survive if you ate. But part of it was just the pleasure you took in it. A grilled cheese sandwich cut into little squares. That was the whole world for you then. You getting it into your mouth was the only thing that mattered. You couldn’t eat it fast enough.”

His father was making him nervous watching him. He hadn’t eaten any of his sandwich.

“You going to sit there and watch me the whole time?”

“No, I’m eating.”

His father took a couple of bites. Connell called for more water and ketchup.

“I wish I could explain it to you,” his father said after a while.

“What?”

“What it’s like to have you. What it’s like to have a son.”

“You going to eat those fries?”

“They’re all yours,” his father said. Connell took some. “Eat as many as you like.” His father slid the plate toward him. “Eat up.”

17

She decided to scrap the intimate dinner they’d agreed upon for his fiftieth birthday and throw a full-scale surprise party instead. One thing it couldn’t fail to do was get him off the couch for a night, but she wanted more than that: she wanted to wake him up, set him on the course to recovering his lost enthusiasm. He’d spent so much time alone lately that it would be good for him to be forced to mix with others.

Until she was drawing up the list for the party, she’d never noticed how weighted toward her side their social group was. So many of the friends they’d lost touch with were Ed’s. When she considered her friends’ husbands, she saw the same thing—a withdrawal, a ceding of the social calendar to the wife. It was her responsibility to ensure that her husband didn’t get domesticated entirely. She would go beyond the usual crowd. She decided to track down some of the guys who were his regular buddies when they first got married and reach out to the cousins he never saw. She would remind him how much there was to look forward to.

She gave her garden box a full makeover, even though she knew the early-March chill would kill everything right after the party.

As she finished patting the soil down around a rosebush, a car zoomed past at a murderous clip bound for Northern Boulevard, salsa music pounding from its four-corner speakers. If she were a man she would have spat in disgust. She hated the driver; she hated the drug cartel he likely worked for; she hated worrying that people taking the train to the party might run into some kind of trouble. God forbid any of them got propositioned by the prostitutes that had begun to walk Roosevelt Avenue. One of them had approached Ed while Eileen and he were coming off the stairs holding hands.

She hoped that the NCB executives she’d invited wouldn’t judge her for her current situation. Her career depended on their seeing her as the kind of person who belonged in their midst. How could she ever explain to them the way Jackson Heights used to be?

She didn’t think of herself as racist. She was proud of her record of coming to the aid of black nurses who’d been unjustly targeted by superiors. She enjoyed an easy rapport with the security guards at NCB, most of whom were black.

She loved to tell the story of her father’s stepping forward to drive with Mr. Washington when no one else would. She also enjoyed recounting the tale of how, when none of the old Irish guard would shop at the Chinese grocer up the block, and the new store was on the verge of failure, her father had paid the man a visit to take his measure. Satisfied that the man, Mr. Liu, was a hard worker and an honest proprietor, her father had stood for a few evenings on the corner near the grocer with the suspect vegetables and stopped people and said, “Go spend some money at the chink son of a bitch’s place,” and they’d listened. Now the whole of Woodside was Chinese grocers. She wondered if the newer generation would do for an Irish immigrant looking to make an honest living the same thing her father had done for one of their own years before. She wondered if some of the black nurses she’d helped along the way would lift a finger for a white woman in need. She’d watched the Bronx spiral downward over the years, and she hadn’t flinched. The security guards marveled at her driving into the neighborhood alone every day. They never let her walk to her car unescorted at night.

No, she couldn’t be called racist. That didn’t mean she had to like what they were doing to her neighborhood. They were making it into a war zone.

The day of the party, her house had never seemed so small. An hour before Ed was supposed to arrive, there was barely room to pass in the halls; she had to ask her cousin Pat to carry a side table down to the basement. Still, as soon as people began assembling in the kitchen, she felt their presence as a kind of armor around her. She tended to the ham and the broccoli casserole in the stove and the separate duty of each pot on the stovetop. She had made nothing to offend anyone’s palate, and so she presented it without anxiety. When the caterer arrived with trays containing more food than could possibly get eaten, she told herself it was safe to begin to relax.

When Connell called from a pay phone and said they were ten minutes away, she was surprised to find herself seized by terror. She passed the news to the living room, which filled with that clamor particular to a crowd silencing itself. A quiet grew louder than the din that had preceded it; she could almost hear her pulse in its murky depths. She moved through the wall of people to be near enough for him to see her when he entered.

As Ed stepped into the room, Eileen closed her eyes, obeying a strange compulsion not to look at his face. A frenzied chorus rang out around her. When she opened her eyes, she saw him beaming and being passed from person to person, shouting as he encountered every new face—shouts like war whoops that could have been either exultant or lunatic. He was red with excitement, and sweat was gathering on him. As she moved close to hug him, she heard him whoop the way he had for the others, as though he hadn’t seen her in years. His whoops went on; they wouldn’t die down. He greeted each successive person with the same ecstatic disbelief.

She was afraid to leave him, afraid to stay. She saw him engulfed in friends’ arms and ducked into the kitchen to get him a drink. When she returned he was miming his own shock for them over and over. She didn’t want anyone else to notice the unconvincing mirth in his performance. She shouted to Connell to cue the stereo. Ed was ushered into the dining room. In the mirror she tried to look at other people’s reactions but was inexorably drawn back to her husband’s expressions. When he saw his brother Phil in from Toronto, he let out a howl that sounded like that of a dying animal. She reached for a tray of hors d’oeuvres to pass. The food smells were mingling successfully; no trace of dust came off any surface she touched; nothing was out of place. The only messes were the ones guests were making themselves—someone bumped into the punch bowl and sent a couple of crystal mugs crashing to the floor—and for those she had great patience.

She poured herself a glass of wine and drifted into the living room, where she gave herself over to conversation. Behind the timbre of any individual voice lay the lovely murmur of the group, but she couldn’t distract herself from the thought of her husband’s frenzied surprise, and she went in search of him.

She went out on the stoop with Pat and the smokers and the kids, but no one had seen him come outside. The bathroom was locked, but after a little while her aunt Margie came out. She went down to the basement and searched its recesses, where she found no sign of him.

When she got back up to the landing at her back door, instead of heading inside she called up the stairs. There was no response, but she had an instinct to proceed upstairs anyway, and she found him sitting on the flight between the second and third floors, just sitting there, looking directly at her as she approached, in a way that unnerved her, as though he’d been waiting for her to find him. The music and talking muffled through the intervening flight rose and fell in waves, following the rhythm of its own respiration. There had been no dip in the revelry yet.

“Frank wants to take your picture,” she said. “Fiona just got here. I don’t know if you saw her.”

He sat in silence, though he didn’t look away.

“Pat’s only here to see you. He doesn’t go to parties anymore. You should have heard him when I finally got him on the phone. ‘For Ed?’ he said. ‘Sure. Anything.’”

“Keep him away from the bar,” Ed said.

“He won’t even come inside,” she said, chuckling. “He’s on the stoop.”

She could feel her eyes watering, though she wasn’t consciously sad. “We’re having a real party downstairs,” she said. “It’d be even better if you were there.”

He patted the spot beside him. The gentleness of the gesture touched her, and being moved when she was also angry confused her, so that she wanted to go back down alone, but she gave in, gathered her skirt under her and sat.

“I’m getting old,” he said. “I can feel my body breaking down.”

“You just feel that way because it’s your birthday,” she said. “Everyone gets old.”

“I didn’t expect to see all these people. I thought we’d have a quiet night.”

She looked at him wryly. “Haven’t we had enough quiet nights lately?”

“I don’t even know half these people.”

“You know almost every single one of them,” she said. “There are maybe four people that you’ve never met.”

“Then I don’t remember them.”

“Of course you do. I’ll go around with you and start conversations and you can hear who they are that way.”

He looked away.

“You love parties,” she said. “You grumble and complain that I entertain too often, but once the party’s going, no one enjoys it more than you. Those people are here to see you. I don’t know what to tell them when they ask where you are.”

“Tell them you saw me a second ago in the other room.”

“What’s wrong with you?”

“I’m tired. I can’t tell you how tired I am. I’m tired of standing in front of a bunch of people and being the center of attention. Do you have any idea how much energy that takes? You’re never off. Never. You can never have a bad day. I feel like I’ve been trying to keep all these juggling balls in the air, and I can’t let them hit the ground or something bad will happen. I’d love to just lie down right now.”

“Well, you can’t. Everyone’s here. We have to make the best of it. I’m sorry I did this.”

“You don’t need to be sorry.”

“I am. This was a stupid idea. Stupid, stupid.”

“I just need the school year to end,” he said. “That’s it. I can’t tell you how much I’m looking forward to vacation. No summer classes for me this year, that’s for sure. I’m just going to stay put.”

Another day, she might have hissed at him to get off his ass and get down there, but something prevented her. She was about to say she’d come back and get him in five minutes when he slapped his knees and stood.

“Okay,” he said. “Let’s go.”

Before they reentered the party, she ran down to the basement to grab a bottle from the rack.

“Wave this around when we get in there,” she said. “In case anyone noticed you were gone.”

Frank McGuire had the camera around his neck and called Ed over, as relieved as a retriever reassembling the pack. She watched him arrange the guys in a row in the dining room, the group waiting for him to focus, and then a moment of stillness that seemed to expand and breathe. She tried to memorize the scene—not the visual details, which she could recall later by looking at the photograph, but the mood, the nimble camaraderie, the way they clutched each other, the hint of annoyance at having to pose, the way afterward they laughed off the brush with intimacy. Every picture of men in a row, she thought, ended as this one did, with them expelled as if by force, dispersing into separate corners to get a drink, a plate of food, to smoke a cigarette. Ed looked vulnerable standing there in the lee tide. She decided not to leave his side for the rest of the party, and ushered him around with a subtle steering of her arm. He was a perfect sailboat, responding to the slightest tug on the line, tacking when she wanted him to tack, coming about when she wanted him to come about. She could feel him relax with her there, and soon she was having fun again. She had to resist her impulse to leave him and head to where the good conversations were taking place. She’d always considered it a luxury that she could count on her husband to entertain himself at parties. From across the room they would check in with each other with a wave, a nod, a wink, and a charge of desire would run through her as she watched the way women’s eyes danced when they were near him. It was hard to see him as well up close; something was lost in the foreshortening.

Cindy Coakley brought the cake in. They sang “Happy Birthday” and Eileen put her hand on his back as he blew out the candles with a remarkable lack of wind, so that a few stray flames survived his second and even third attempts. The lights came on and Cindy passed him the knife. He stood for a moment brandishing it before him, and Eileen couldn’t help finding something menacing in the image. She put her hand over his in what she hoped would look like an evocation of the gesture of unity with which they’d cut their wedding cake, and she pressed his hand down into the thin layer of frosting and the forbidding brick of ice cream beneath it. When she released her hand he struggled to free the knife from that frozen denseness and, failing, threw up his palms in defeat and took a step back from the cake. She laughed with an expression she hoped said something universal and vague about the uselessness of men and took his face in her hands and gave him a big, unrestrained kiss. To do so in front of all those people went against every ounce of culture she’d ever absorbed. He stiffened at first, but then he relaxed and let her kiss him. People began hooting and cheering. She let him go and pulled the knife from the cake and started serving little slices.

She hated to wake up to a messy house; it felt like paying a bill for something consumed without being savored. Still, when the last guest left, she went straight to bed. Ed slept on his back, inexorably flat. It was nearly her favorite thing about him. She’d read that it took confidence to sleep on one’s back, because it exposed the internal organs. He’d always been confident in bed. She loved how small he made her feel, how she could nestle up to him and be enveloped in his reach. She thought of the first time they’d danced, her surprise at his size, which he had hidden in his overlarge jacket. He had a rangy athleticism that put him at ease in the company of men who made their living with their hands. He allowed her to bridge two worlds, the earthbound one she’d come from and the rarefied one she aspired to. And he was the only man in whose arms she’d ever been able to fall asleep.

Начислим

+20

Покупайте книги и получайте бонусы в Литрес, Читай-городе и Буквоеде.

Участвовать в бонусной программе