Книгу нельзя скачать файлом, но можно читать в нашем приложении или онлайн на сайте.

Читать книгу: «Letter To An Unknown Soldier: A New Kind of War Memorial»

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers,

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins 2014

Introduction © Neil Bartlett and Kate Pullinger 2014

Letters © individual contributors 2014

Photographs of statue © Dom Agius 2014

Neil Bartlett and Kate Pullinger assert the moral right

to be identified as the editors of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

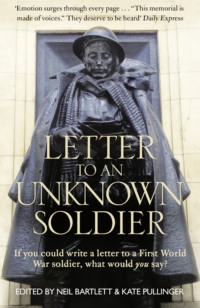

Cover shows: photo of statue © Kate Gaughran;

letters © individual contributors 2014

Designed by Kate Gaughran

Letter to an Unknown Soldier was produced in association with

Free Word and commissioned by 14-18 NOW, WW1 Centenary

Art Commissions, supported by the National Lottery through

Arts Council England and the Heritage Lottery Fund

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008116842

Ebook Edition © November 2014 ISBN: 9780008116859

Version: 2015-10-06

Dedication

Dear soldier …

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Letters to an Unknown Soldier

Afterword

List of Contributors

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

Introduction

Our inspiration couldn’t have been simpler.

On Platform One of Paddington Station in London a famous First World War memorial by Charles Sargeant Jagger features a life-size bronze statue of an unknown soldier in full trench uniform. He is reading a letter; no one knows who his letter is from, or what message it contains. In the weeks leading up to the hundredth anniversary of Britain joining the war – in a year crowded with official remembrance and ceremony – we invited everyone in the country to pause, take a moment or two, and write that letter.

People responded in their thousands. Some wrote physical letters and posted them to the soldier at Paddington Station; the vast majority posted their letters online to a specially created website. In the thirty-seven days between the 28th of June 2014 (the centenary of the Sarajevo assassinations) and the 4th of August (the centenary of the declaration of war), the soldier received over twenty-one thousand letters. They came from across the country and around the world, and from everyone; from railway workers, writers, schoolchildren, serving soldiers, prisoners, nurses, pensioners – and the British Prime Minister.

The inspiration behind the project may have been simple, but as you will see as soon as you start to read the letters that we have chosen from those thousands for this anthology, people found responding to our invitation far from straightforward. The obvious question of ‘What shall I say?’ quickly splintered into many more. How can I write if I am not a writer? How can I talk about something as big as war? How should I address a dead person? Do I have to travel back in time and imagine I am writing my letter in 1914, or should I write from now? Am I writing to one man – to a particular named individual from my own family history perhaps – or to all the army of the dead? Is the soldier white, or is he black? Is he British, or Canadian, or Indian, or from the Isle of Lewis? And so on … The beauty of the idea turned out to be that the archetypal and archaic literary form of a letter entitled people to answer these and many other questions in their own utterly individual ways. A letter is not a text message nor a ‘like’ on Facebook – in order to write one you have to stop, and think, and feel, and compose not just your letter but yourself. A letter is also not an essay nor a short story. A letter is a page or two long, with a beginning and an end. A letter is private. A letter is everyday. A letter is familiar. A letter is, above all, personal.

All of the letters that the soldier received during the thirty-seven days that the website was open for submissions were published without censorship or alteration or editing. In creating this anthology, we have resisted any temptation to organise our chosen letters by theme or place of origin. A bewildering diversity of voice and form was as characteristic of the soldier’s daily postbag as the frequent reiteration of often familiar tropes, images, phrases and sentiments. That’s why you’ll find the letters we’ve selected in no obvious order, with a politician’s letter next to a schoolchild’s, a queer love-letter next to a military salute, a soldier’s wife next to a pacifist pensioner.

Letter to an Unknown Soldier was commissioned by 14-18 NOW as part of its five-year cultural programme responding to the centenary of the First World War. The entire archive of letters will remain on the current website until 2018, which means that if you want to read more of them all you have to do is go to www.1418now.org.uk/letter/ and start reading. After 2018, the website – including all 21,439 of the letters – will remain part of the UK Web Archive, provided by the British Library. There it will remain permanently accessible, providing future readers with a vivid snapshot of what people across this country and across the world were thinking and feeling in the weeks leading up to the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War. They give us a glimpse of what it means to remember a war that is no longer within lived experience; what it means to remember what cannot in fact be remembered.

Remembrance is usually conducted in silence. This memorial is made of voices – numerous, various, contradictory, heart-broken, angry, sentimental and true.

Neil Bartlett and Kate Pullinger,

November 2014

Letters to an Unknown Soldier

Dear Unknown Soldier

Imagine you could read my letter now and see how far the world has come since you were fighting in the war. You may have been Unknown then but not now because you have millions of people writing you letters in which most of them are expressing their feelings for you and saying how much of a good person you are.

If I could meet you now there would be so many questions I would ask you but for now here are just 3.

1. What was your family like?

2. What did you like to do?

3. Who were you fighting for?

Shane Cook

14, London, Holloway School

Dear Owen

Your mother called today, I wish I’d been out.

Anyway I made her welcome.

She sat in your chair, I don’t know if she was trying to make a point.

You were very quick off the mark to sign up with your pals.

Not a thought for me or the kids.

Why didn’t you take all the clothes I’d laid out for you?

You’ve only got one pair of smart trousers.

The heavy thick coat is still where you left it.

Your mother said you’ll catch your death, what do I care?

And you’ve left the back gate off its hinge, well I’m not going to fix it.

Anyway I will send you the back pages of this week’s Gazette Times.

Mind you by the time you get it the runners and riders have already run.

I saw the postman again today, I hung out the washing, as all the women do, we all watched him pass, then we all went back inside.

God Bless.

Mary

Mary Moran

Sheffield

You don’t know me yet, but I have things to tell you. You’re about to go back, and I’m sorry to say it’s going to be worse than ever this time. You’re going to be wounded, I’m afraid. Very badly. But you’ll survive. You’ll make it home. You have to, you see. Forty years from now you’ll become my grandfather.

Not that home will be a bed of roses. Wages will be down, and three men will fight for every job. At times you’ll be cold, and at times you’ll be hungry. And if you say anything, they’ll come at you with truncheons.

And then it will get worse. There are some lean years coming. And I’m sorry, but along the way you’ll realise: the war didn’t end. It was just a lull. You’ll have to do it all again. This time your son will have to go, not you. You don’t know him yet, but you will. But don’t worry. He’ll get back too. He has to. You’re my grandfather, remember?

And I’ll be born in a different world. There will be jobs for everyone. They’ll be building houses. You’ll go to the doctor whenever you want. I’ll go to school. I’ll get free orange juice. You’ll get free walking sticks. But most of all we’ll get peace. Finally, year after year. I will never go to war, you know. I will never have to. The first time I go to France will be a trip with my school.

So go back now, and play your tiny part in the great drama, and sustain yourself by knowing: it comes out well in the end. I promise.

Lee Child

Writer

Dear Soldier

You are strong and brave. You are going to face unknown terrors because you have been told that you are protecting your home and family by fighting the threat of domination and oppression by a foreign foe.

Your finest emotions of loyalty and courage have been subverted by power-hungry empire builders, both politicians and monarchs.

The same lie has been perpetrated in France, Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia, and will be spread across the globe.

Consequently brave young men across the world have been led to believe that they are doing the right thing by killing one another.

If you could see into the future you would know that this will happen time and again. Young men, and some women too, will be manipulated by those in power to commit murder for the sake of King and Country/the Fatherland/the Revolution, or for Jihad.

You don’t have any quarrel with those young men who speak different languages and have different religious beliefs.

I am asking you to be even more brave.

TURN BACK.

GO HOME.

Show that you can see through the propaganda and that you are not prepared to kill or die for the greed and selfishness of the ruling class.

Meantime, I wish you well and hope that you return safely, and don’t come back like my grandfather, whose mental and physical health were ruined after nearly four years at the front.

With love,

Anna Sandham

Anna Sandham

70, Oxford, Grandmother

The letter I didn’t send

Dearest Luke

As I watched you walk away with all the other men, marching off to France, I thought I would die from pain. I wanted to wrench you out of that line, take you home to where you belong and know that you would always be safe, and always be you.

This fighting is not for you. You have never been a violent person, you are the most kind and gentle man I have ever known and this will do violence to your soul. I am so afraid that you will come home with nothing behind your eyes but horror and a heart so bounded by stone and afraid of the worst that can happen to people. You would never let yourself love anyone again, through fear of the horror.

I think I fear the damage to your soul as much as I fear you dying. How terrible it would be to live the rest of your life with nightmares, screaming terror and despair.

May God be with you always,

Mum xxxx

The letter I did send

Dearest Son

How proud I was of you as you marched off to defend our country from the Germans, and how wonderful you looked in your uniform. We are all thinking of you, my dearest son, and of the adventures you will have in France. Maybe you will learn a little of the language and eat some wonderful food.

You will be in my thoughts and prayers every minute of every day, my darling boy. Stay well and come home safe to us.

I love you and may God bless you always,

Mum xxx

Sue Oxley

64, Glastonbury, Mother

For my father, who did fight in a war and who came home damaged in his soul.

There you stand, a monument to so many who never returned. Did you leave home whistling, upbeat and expecting adventure? Were you there at the outset, when people still believed the war was just and would be over in weeks, or months at most? How quickly did you realise you had been sold a lie? I look at you and wonder who you knew – did you serve with pals from home, all in together and watching out for each other, or did you join up far away from those who knew you, because you had something to hide? Did you by chance meet a boy called Cyril from Cornwall, who would have claimed to be eighteen, but who was just a child of sixteen? Did you, like him, leave the safety of your hometown to sign up in London, away from the friendly local recruiters, who knew your age and sent you home to your mother? How many were there like him in your unit? How many of them made it home, like he did? How many went on to have children, like Cyril’s daughter, my mother?

You can’t tell me, of course, but let me tell you something. We still recruit children today, but we do it openly, seemingly without shame. We have learned nothing from your suffering and sacrifice; recruitment remains a numbers game. Children sign up more willingly, they ask fewer questions, and they get paid less. The ones who join up at sixteen these days often don’t have many life chances. They are too young to vote, but apparently old enough to serve. My grandfather Cyril was just a boy when he ran away to fight. What an indictment it is on our society that, one hundred years after he joined up, we have not progressed enough to apply the simple maxim ‘Children, Not Soldiers’ to our own Armed Forces. I’m glad you can’t understand, because I believe that if you knew how little has changed, then you, like me, would feel ashamed.

Demelza Hauser

45, St Albans, Mother

I sit on the Board of a charity which works to prevent the recruitment of children into armed forces across the world. My grandfather’s story of running away from home in Cornwall at sixteen to join up in London is part of our family history. He died when I was very young, so I never had a chance to ask him about his experiences in the war. It makes me sad that a hundred years after my grandfather was a child soldier, we still recruit children into the Army.

Somewhere in the world somebody is walking on the place where you fell. Or maybe they are lying on their back, face turned to the sun, picnicking with beer and sandwiches. Do crops grow on your grave? Cows move slowly across it? Does a farmhand bend to pick up a bullet casing and put it in her pocket? Has the minefield been ploughed over or left fallow? Are homes built there? Is there a town where once there were battlefields? Fields where once a town stood? Across five continents, one hundred years before you were sent into battle, and one hundred years since, and before and after, and before and after again, lying between layers of earth, under sand dunes, rocking upon the seabed, buried beneath rubble, incinerated into dust: the bones of the fallen. Almost anywhere in the world, wherever one of the living stands now, a warrior has fallen.

We have forgotten their names: The Unknown Warriors. I wonder, at night when the station is still, do they appear from all directions? Dressed in uniforms of every kind, camouflage to cotton and followed by others dressed in the clothes of everyday, farmers’ overalls and jeans, business suits, high-heeled shoes, djellabas, rubber flip-flops and leather sandals, shorts, tunics and T-shirts, trainers, sports clothes and sun hats. I wonder if one day there will be another statue standing alongside you, to those people who fell beyond the battlefield, who were queuing for bread when the shells struck, or serving dinner to hotel guests at a poolside restaurant when a grenade was thrown, crossing the street when they were sighted through the crosshairs of a sniper’s rifle, sitting in front of their office computer when the first plane struck, shopping in a mall when armed gunmen burst in, walking to the fields when they trod on a mine, buying fruit in the bazaar when the suicide bomber passed by.

Would you even recognise this new kind of warfare? As you board your train to France and the trenches, did you ever imagine it would come to this? Will there come a time when we will commemorate them, lest we forget: a statue, a tomb for them too, uncounted, countless? The Unknown Civilians.

Aminatta Forna

London, Writer

Stay safe. Get back. Bring as many back with you as you can manage. Nothing else matters.

Sean

25, USA, US Army, Infantry

For Nathan. I’m sorry I wasn’t there, dude. Things might have gone differently.

Hello Tommy

I never knew you, but my Grandfather, Fred, joined up, like you. He’d been a miner and worked at the pithead at Senghenydd – leaving just before 440 died in the explosion on 14 October 1913. He’d left the colliery to go and work in Dundee, where he also joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, before emigrating to New Zealand in 1911.

Three years later, war broke out in Europe and after working as a gold-digger and miner in New Zealand, Fred joined the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs) as a field artillery driver. This involved driving a team of horses pulling a gun carriage into the field of battle. A few days after joining up there was an explosion on 12 September 1914, at the Ralph Mine in Huntly, where he had been working, claiming the lives of 43 men. He must have sensed then that he had some form of charmed life.

Fred served at Gallipoli and at the Somme, where he was injured and hospitalised. Like so many others he never spoke of it afterwards. A million soldiers died or were wounded during the Battle of the Somme, and 100,000 died at Gallipoli, so it’s incredible that Fred survived both campaigns, albeit with injuries.

After being evacuated to England on medical grounds, Fred was visited in hospital by Sarah Jones, who was raised by his half-sister after her own mother died. They fell in love and wanted to marry, but Fred was forced to New Zealand before he could be officially discharged by the ANZACs. Before he returned to the UK he worked for the Wellington City fire department.

Fred made it home to Britain safely and married Sarah in 1919. They settled in West Chislehurst, a suburb of south-east London, and had six children, the youngest being my father. Never one to shy away from danger, Fred joined the London Fire Brigade and received a bronze medal in recognition of his ‘long and zealous service’. Fred served during the Blitz of the Second World War and must have faced considerable danger most nights. He suffered a number of shrapnel wounds while fighting fires during the war.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Начислим

+16

Покупайте книги и получайте бонусы в Литрес, Читай-городе и Буквоеде.

Участвовать в бонусной программе