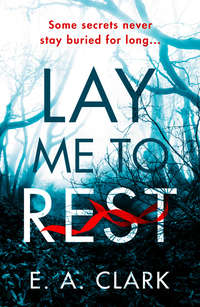

Читать книгу: «Lay Me to Rest»

Some secrets never stay buried for long…

Newly widowed Annie Philips is plagued by the memory of her husband. But she carries a larger burden… Weeks after his death, she discovers she is pregnant. When Annie is unable to recover from depression, her sister, Sarah, suggests a healing retreat in the Welsh countryside, recommended by Sarah’s colleague, Peter. It is here that she becomes a house guest of the kind Mr and Mrs Parry – along with the enigmatic Peter. Friendly. Alluring. Mysterious.

As Annie settles in to the Parrys’ home, and grows closer to Peter, she becomes increasingly aware of another presence… a supernatural one. Annie becomes the target of violent disturbances that begin occurring in the house. Until one day, when she is drawn into an open field where she uncovers a box.

A box no one was ever meant to find.

Can Annie solve the mystery she has become tied to? Or will the sinister forces surrounding the house claim her life, and the life of her unborn baby?

Don’t miss this chilling new tale from E. A. Clark, perfect for fans of Amy Cross, Shani Struthers and Andrew Michael Hurley.

Lay Me to Rest

E. A. Clark

ONE PLACE. MANY STORIES

Contents

Cover

Blurb

Title Page

Author Bio

Acknowledgements

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Epilogue

Glossary

Endpages

Copyright

E. A. CLARK lives in the Midlands with her husband and son, plus a rather temperamental cat, a rabbit and a chinchilla. She has three (now grown-up) children and five grandchildren. She is particularly partial to Italian food, decent red wine (or any coloured wine come to that…) and cake – and has been known to over-indulge in each on occasions.

She has a penchant for visiting old graveyards and speculating on the demise of those entombed beneath. Whilst she has written short stories and poetry for many years, a lifelong fascination with all things paranormal has culminated in her first novel for adults, Lay Me to Rest. The setting is inspired by her love of Wales, owing to her father’s Celtic roots.

I would like to thank my family for their patience! Also, the lovely Rayha Rose for her help and invaluable guidance, and the rest of the editorial team at HQ Digital. I am also very grateful to Michelle Magorian for her kind words of encouragement.

This book is dedicated to the memory of my dear mum,

with all my love and thanks for everything she did for us.

We miss you.

Prologue

July 2009

Anglesey, North Wales

Deep into the night, the rain fell unremittingly. I lay still, listening as it battered the windowpane: a steady, rhythmic thrum. Since childhood, to be safe and warm within had always been a source of comfort to me during a storm, knowing that the angry deluge could not penetrate the walls – that I was protected from even the harshest force of nature.

But suddenly the pattern began to change. The sound was infiltrated by a slow, persistent scratching. As the noise increased in frequency and intensity, heart in mouth, I eased myself from the bed and crossed the room, hardly daring to draw breath as my trembling hand reached for the curtain.

It was happening again. Cold terror surged through my veins as a pair of dark, glowering eyes met my own through the glass. As far as I was from the site of the haunting, it would seem I was to be afforded no respite from her malevolent influence. I could feel her drawing closer. I staggered back from the window, my fear knowing no bounds as I became suddenly enveloped by the familiar incipient chill; inhaled the cloying, musky fragrance that I had come to dread.

I opened my mouth to scream, but my throat was so dry that I could emit no more than a pitiful croak. It was inconceivable that I should find myself once more in this position; the previous disturbing encounters of the supernatural had been enough for anyone’s lifetime. I had foolishly believed myself beyond harm here; that she should have followed me was unthinkable. Was there no refuge to which I could safely retreat?

My hands shook violently as I tried desperately to turn the key in the lock; but it was stuck fast. I whipped round, panic-stricken now, my back pinned to the door. Through the gloom I could still discern the menacing presence, initially a pallid shadow against the opposite wall, shapeless and pulsating. But I could feel her getting closer. Even without seeing clearly, I knew without doubt who she was. She exuded loathing and contempt, sentiments for which I had apparently become the sole focus.

The walls seemed to close in on me now. My heart hammering, my breath came in shallow, rasping gasps as I watched the silhouette become ever clearer and more recognizable. The mocking eyes seemed to penetrate my very soul. Despite my best efforts, my feet remained inert. I felt the ground draw me like a magnet. Instinctively, I cradled my stomach; the room swam as she seemed to surround me.

And then I knew no more.

June 2009

Birmingham, West Midlands

I awoke, as had become the norm of late, cheeks wet, with fresh, hot tears spilling from my eyes, a choking sob rising in my throat. Each night the same recurring dream – Graham, standing at my bedside: expressionless, staring down at me. But the leaden weight of my arms left me unable to reach out to him and he would fade away, leaving me alone once more.

It was still dark and only a sliver of lamplight could be seen through the narrow gap between the curtains. Shrugging the covers around my shoulders, I slid out of bed and walked across to the window. I stood, staring, for what seemed like an eternity, down at the deserted street below, absent-mindedly resting my hands on my swollen stomach.

As daylight gradually began to creep through, I shifted my gaze, only to be met by my own dishevelled reflection in the glass. I suppose, looking back, that this was the wake-up call I so desperately needed.

The gaunt, transparent image staring back at me was virtually unrecognizable. For more than three months I had lived like a recluse, neglecting my appearance and more or less subsisting on a diet of anything and everything that could be tipped straight from a can or packet, supplemented in the last fortnight (on the insistence of my younger sister) by Prozac, prescribed by a concerned locum whom she had called to the house.

In spite of my initial reluctance to take the tablets, having passed the first trimester of my pregnancy, I was assured that the risks to the baby were very small compared with the jeopardy to my own mental health if I remained untreated.

*

As of the night of 25th February 2009, my status had become officially demoted from that of wife to widow. The title was something that did not sit well with me – it was a word I had always associated with women in their dotage who had shared a whole lifetime with their partners. At the ripe old age of thirty-six I was struggling to cope with this new-found and unwelcome identity thrust upon me by events beyond my control.

Finding myself unexpectedly and miraculously pregnant just seven weeks after my husband Graham’s fatal accident left me reeling. My monthly cycle had always been predictably erratic, therefore another late period was nothing new; nor had I experienced any of the associated symptoms such as strange cravings or nausea. After years of talking indifferently about the possibility of having a child, when I had eventually thrown myself wholeheartedly into the process of attempted baby-making, our efforts had remained fruitless.

The loss of my husband had totally devastated me. That, coupled with the untimely discovery of my pregnancy, had propelled me into a state of turmoil. A whole wave of emotions now washed over me: the baby would never know its father, and Graham, who had so desperately wanted to claim that role, would never be there to watch our child growing up.

Plus, if I were to put hand on heart, I did not know how I would cope with rearing a baby on my own. I had always been a career girl and the daunting prospect of single-handed responsibility for the welfare of a helpless infant threw me into a blind panic. I was a mess.

*

‘You really can’t go on like this, Annie,’ Sarah had told me only the previous morning, as she opened the curtains and attempted to restore some semblance of order to the train wreck that was once my living room. She turned her head to one side in that way of hers and looked at me, sympathy emanating from every pore.

‘You have to try to move on,’ she said, gently. ‘I know it’s hard, but you really need to get back to some sort of normality. He wouldn’t want you to be so unhappy. You’re still a young woman. And you’ve got to think of the baby, too.’

*

She had been right, of course. My sister: ever the voice of reason and practicality. We were so different in both appearance and nature. She, fair-haired and slight, like our mother; equable, ever the optimist. I had always been what our father had diplomatically described as ‘well built’, my paternal genes leaving me narrow-waisted but short in stature and solid of limb, and darker in both colouring and temperament. I was definitely of the ‘glass half-empty’ school of thought, whilst Sarah always maintained that something positive could emerge from any situation if one allowed it to.

Our parents, both suffering from arthritis, had retired and emigrated to Florida to escape the British climate and were therefore too far away to offer much assistance. I was acutely aware that I had begun to lean heavily on my sister for support and felt guilty about it. The least I could do was listen to her advice.

I leafed through the brochure of holiday lets, which Sarah had well-meaningly brought to show me the other day, the slip of paper still clipped to the page that she had been so eager for me to see. It did look tempting. An old stone cottage with a wisp of smoke climbing from its chimney and roses woven into a trellis round the door. It was set a little way up a hillside on farmland in Anglesey, North Wales, surrounded by views of lush pastures and white-capped mountains.

‘It could be just what you need,’ she had said, hopefully. ‘Peter has holidayed there on and off for years. His father’s family were from the area, you know. He spent a couple of weeks there last August and said it was wonderfully restful. You have the cottage all to yourself, with the farmhouse right next door for home cooking – and company, if you feel like it. Peter said the old farmer and his wife are a real tonic. Clean air, beautiful scenery: what more could you ask for? And Peter’s even offering to drive you up there himself!’

I had paid little attention at the time, but maybe the Prozac was starting to kick in. Perhaps it was time to give myself a shake and get back to the real world. As if to reaffirm my thoughts, the baby delivered a sudden sharp kick into my ribs.

I hesitated for a moment before picking up the telephone.

‘Sarah? I’ve been thinking … Can you come over? I need to get in touch with Peter …’

Chapter One

July 2009

And so it was that, on the first Sunday in July, I came to be a passenger in the car of my sister’s friend and colleague, Peter, heading for what I hoped would hail the beginning of a fresh start for me.

The doctor had warned me not to drive if the medication seemed to be affecting my judgement and I did not as yet feel confident enough to get back behind the wheel, so I was relieved and grateful when Peter had offered to take me. The agreement was that he would be staying just the one night in the farmhouse itself, and then Sarah would join me in a few days’ time and stay in the cottage for the remainder of the let, which had been booked for three weeks.

I didn’t know Peter particularly well. He had been working in the same office as Sarah for the past few months. We’d met only once or twice when she had brought him to the house. He was in his early thirties, of medium height and build; dark-eyed, and handsome, in a quirky sort of way. I found Peter pleasant enough and polite, but today, evidently having been briefed by Sarah about my state of mind, he seemed a little awkward about making conversation.

I didn’t mind. Still in that semi-anaesthetized state induced by the initial effects of the antidepressants, I welcomed the opportunity to sit back and watch as the flat, soulless terrain of the industrial Midlands with its grey, suffocating factory chimneys and incessant traffic, gradually gave way to a vast expanse of clear sky with high, cotton-wool clouds, and the undulating patchwork of fields of green and gold of the border country, peppered with sheep and cattle grazing contentedly.

The gentle pitch of the hills and dales soon swelled into a majestically mountainous region of peaks and troughs, as the landscape became wilder and more ruggedly beautiful. I had always enjoyed sketching and thought briefly what a wonderful picture the view would make.

We crossed the imposing silver-grey suspension bridge that traversed the body of water separating the island from the mainland. I gazed down at the scene beneath us. The Menai Straits, dark but calm as a millpond, glittered in the late afternoon sun. Several small, colourful boats were moored at either side of its banks. They bobbed slightly with the gentle movement of the current. Numerous houses were staggered on the opposite embankment, their windows winking in the sunlight.

Peter became a little more animated.

‘Not far, now! I’m so glad it’s such lovely weather – it makes all the difference to the cottage, seeing it in on a bright day. Not that it should matter,’ he added hastily. ‘It’s just that, well, first impressions of a place can colour your judgement, don’t you think?’

I felt the corners of my mouth twitching in amusement. He was clearly anxious for my approval of the house, since he had recommended it so gushingly to Sarah. Although their relationship was platonic, I suspected that Peter would like it to be rather more, but I knew that his feelings were sadly not reciprocated. Sarah had apparently long been holding a candle for some mystery man and showed no interest in anyone else. I often worried that she would finish up embittered and alone, although she seemed content enough with her lot.

‘I’m sure it’ll be beautiful. The scenery looked breathtaking in the brochure,’ I said, smiling to myself.

Smiling. For so long it had felt as if I would never smile again. Sarah knew me better than I knew myself. A change of outlook – always helps people see things from a different perspective, she had told me. It seemed she might well be right.

I felt an increasing sense of anticipation as we drove across the island. Peter was keen to point out various landmarks, and signposts to places that he thought I might find of interest.

‘Of course, you don’t really need to go anywhere else,’ he added. ‘The farm has a huge acreage, and there are plenty of great walks across its fields. Will and Gwen – Mr and Mrs Parry – are lovely and they make you so welcome. But you’ll find that out for yourself soon enough.’

We had taken a right turn at the roundabout a mile or so after crossing the bridge, climbing a steep incline past a high school on our left and a housing estate to the right. Reaching the top of the hill, we turned right yet again at a crossroads.

Most evidence of human occupation seemed suddenly to disappear. The road meandered waywardly like the course of a river, rising and falling with views of nothing but verdure and livestock, and the occasional crumbling edifice, beyond low, rough stone walls and hedgerows, for what seemed like miles. Each junction was a tributary, twisting tantalizingly from view.

Peter began to brake suddenly and turned left off the main road through an entrance largely obscured from the highway by a rather neglected hawthorn hedge. The car wheels rattled over a cattle grid and through an old iron gate, held open against a sturdy wooden post with a thick loop of frayed rope. From the centre of the gate, a battered nameplate swung from a rusty chain, over-painted in white capitals with the words ‘Bryn Mawr’.

‘There it is!’ he announced, pointing to a huge white farmhouse at the end of the narrow, roughly tarmacked track, some two hundred yards in front of us. ‘And that’s the cottage. Look.’

To the left of the main house and its outbuildings, a short distance across a field and slightly elevated on a gentle slope, stood the diminutive pale grey stone building. It looked exactly as it had appeared in the photographs.

‘They call it “Tyddyn Bach”,’ Peter informed me. ‘It means “Little Cottage”, apparently.’ He grinned. ‘How twee!’

I almost laughed. I wasn’t quite there yet, but my mood was definitely lifting.

Mr and Mrs Parry were a couple in the autumn of their years, ruddy-faced and stoutly built, with the whitest of hair. I found them quite charming, almost like a pair of old bookends. Inexplicably, there seemed to be an air of quiet sadness about them. They embraced Peter like a long-lost son, and shook me warmly by the hand.

‘Peter’s told us all about you, Mrs Philips,’ said Mrs Parry, beaming. Peter shot her a warning glance, but she clearly intended to make no reference to my fragile mental health, or to my recent bereavement. ‘You’re a teacher, I believe? And I understand you like to draw – Peter says you’ve done some wonderful pictures …’

I smiled. ‘Well, I like to dabble a little – I find it relaxing. Which teaching most certainly isn’t these days!’

‘Well, you’re sure to find plenty to inspire you round here! I do hope the cottage lives up to your expectations. But first things first – come on in and have a cup of tea. I’ve just made scones and crempog – and we’ll all have a proper supper after you’ve had time to unpack.’

‘You’re very kind,’ I said. ‘But do call me Annie.’

An almost imperceptible glance was exchanged between the old couple, but neither said a word.

‘I’ll join you all in a minute,’ said Peter. ‘Just let me take … er … Mrs Philips’ stuff over to the cottage for her. Gwen, have you got the key there, please?’

Mrs Parry delved deep into the capacious pocket of her apron and produced a large, old-fashioned brass key. She handed it to Peter.

‘Don’t be long, then,’ she said, with a smile, ‘or your tea’ll get cold.’

Peter heaved my case from the boot of the car and crossed the field, then crunched over the rough shingle footpath, which had been laid as far as the entrance to the cottage. I watched as he seemed to pause for a moment, looking up as though deep in thought, and then disappeared through the doorway.

I hovered momentarily, unsure whether I should follow.

‘Come along, cariad. I’ll take you over and show you where everything is, once you’ve had some refreshments.’

Mrs Parry led the way over to the main house. I had no appetite, but not wishing to cause offence said nothing, and trailed obediently behind her. I was ushered into a sizeable scullery, where the comforting smell of baking filled the air. It was a typical, old-fashioned farmhouse kitchen, with whitewashed stone walls, and copper saucepans and utensils suspended from a frame attached to the ceiling.

In the centre of the brick-red-tiled floor stood a rustic wooden table, spread with a red and white gingham cloth. A shaft of dwindling sunlight filtered through the small window above the old porcelain sink, washing the heart of the room with a subtle, rosy hue. A huge copper kettle whistled persistently on an ancient blackened range.

I perched uneasily on a particularly hard oak chair proffered at the head of the table. There was never any chance of an awkward silence, as Mrs Parry bustled about, chatting away nineteen to the dozen. She told me that I would be the first person to occupy the cottage since Peter had left last summer; that it stood empty for much of the time these days.

At the end of the last holiday season, Mr Parry had concluded that they should no longer advertise it as a holiday let, since neither he nor his wife were getting any younger. The occasional ‘word of mouth’ occupation might be all right, but it was becoming too much like hard work – ‘Present company excepted, of course!’ said the old woman, with a wink.

The weather, I was informed, as she handed me a plate of warm, buttered scones and pancakes, was improving by the day and there was promise of a heat wave in the next week or so.

‘Milk and sugar?’ She beamed, as she poured strong, steaming tea into a china cup. I nodded, a little overwhelmed.

Mr Parry had seemed content to let his wife monopolize the conversation. He reclined in an old armchair near the stove, his rheumy blue eyes crinkling into a smile, as he drew on his pipe. The occasional puff of aromatic smoke escaped from the corner of his mouth, creating a fog around his weather-beaten countenance. He looked like a caricature, with his battered flat cap, and heavy working boots in which his feet were propped, crossed at the ankles, on an old, three-legged wooden milking stool. Suddenly, he spoke.

‘Have you ever visited the area before, Mrs Philips?’

My request to call me by my first name had apparently been either forgotten or ignored. Or perhaps it was just that Mr Parry came from that generation which considered it impolite to address a stranger by anything other than their formal title.

His voice was gravelly and deep, the words slow and deliberate, with a pronounced northern Welsh lilt. I thought back to the time when Graham and I had spent ten days in Ireland. We had taken in a few nights’ stay at a hotel on the far side of the island, en route to the ferry port.

‘Just the once. My husband brought me a few years ago …’

The memory of that lazy, happy time flooded back. It was mid-May and the trees were in full leaf. Graham had been in buoyant spirits, having recently completed a successful and prominent piece for the newspaper he was working for. I had just received notification of an imminent pay rise and we were both feeling pretty pleased with ourselves.

We had driven north at a leisurely pace, stopping for the odd tea break and photo opportunity. I rarely let my hair down completely, but the mellow spring weather and beautiful scenery were conducive to total relaxation. We took breakfast in bed every day and enjoyed long walks on the beach. Our lovemaking was frenetic, just as it had been in the first flush of our relationship. It was as though we were rediscovering one another.

I put a hand to my neck, remembering the beautiful necklace that Graham had bought for me when we arrived in Ireland. It was a thoughtful, spontaneous gesture and I had been really touched. I loved him so much.

A tight knot was forming in my throat and tears welled in my eyes. For the briefest while, I had managed to put him to the back of my mind for the first time in months.

Without a word, Mrs Parry came over and gently placed a hand on my shoulder.

‘Peter told us about your loss. We understand just how you feel. You see, our son, Glyn, passed away – almost ten years ago, now. The hurt never goes away, you know, not completely. It’s always there, just under the surface, waiting to jump up and sting you when you least expect it. So you feel free to have a little cry whenever you need to. You’re among friends here.’

She smiled, a touch wistfully, and I felt at once grateful and a little more at ease.

‘Didn’t someone say something about tea? I’m gasping!’

Peter had appeared in the doorway. Mrs Parry chuckled as he took his place adjacent to me at the table. She handed him a huge mug, then promptly began to regale him with tales of all that had taken place since his last visit.

Still in something of a haze from the effects of the antidepressants, I leaned back in my seat, half-listening, half-daydreaming.

As I surveyed the room, I noticed several black and white family photographs hanging on the wall near the door: Mr and Mrs Parry in their younger years; Mrs Parry proudly showing off a plump, smiling baby wrapped in a crocheted white shawl; Mr Parry shaking hands with an official-looking gentleman as he was presented with a prize of some sort at a county fair; and, on closer inspection, one of a longer-haired and youthful Peter, accompanied by a grinning, open-faced boy of around twelve or thirteen crouching in the foreground, with one hand resting atop the head of a panting Border collie.

‘Mrs Parry – is that your son in the photograph with Peter?’ I ventured.

The old lady turned to look at the picture and smiled.

‘Oh, yes. Glyn and Peter here were great pals, weren’t you? There were only nine months or so between them. We had Glyn quite late in life, really. He didn’t have any brothers or sisters, and neither has Peter, and the two of them became friends when Peter used to come and stay with his parents. They’d disappear for hours with that old dog.’

She stared pensively at the photograph for a moment and then turned to Peter. ‘Wasn’t that taken the day you found the box in the field?’

Peter nodded, gulping down the last of his tea. ‘That’s right. Floss sniffed it out.’

I sat up, mildly interested. ‘What box was this, then? Was there anything in it?’ I asked. Peter shifted a little in his chair and appeared to be avoiding eye contact.

‘Oh, some old tea caddy, with just a few coins and stuff inside. Buried treasure, we thought it was at the time. But we were only kids. There was nothing of any real value in it, unfortunately.’

‘Whatever happened to that old box in the end? D’you remember what Glyn did with it, Peter?’ Mrs Parry’s brow furrowed into a frown as she tried to recall.

‘No idea,’ said Peter, dismissively. He rose somewhat abruptly and clapped his hands together as if to show that he meant business.

‘Right, aren’t you going to show your guest round “Tyddyn Bach”, then?’ he said, evidently keen to move on from this latest topic of conversation. He looked pointedly at his watch, which I alone seemed to recognize as a less than subtle hint.

Mrs Parry appeared oblivious to his discomfort. ‘Yes, of course. Here I am chattering on and I bet you’d like a wash and brush-up before supper, wouldn’t you?’

I agreed feebly and was promptly led from the house over to my new temporary abode by Mrs Parry, who continued talking all the while. The air was balmy, but the sun was beginning to wane now, leaving the stone walls of the cottage tinged with a faint pink glow, which reflected the marbled sky of the approaching evening.

‘It looks very pretty,’ I remarked, as we trudged towards the cottage with its pink rose arch. Above the wooden door, which was freshly painted in a deep blue, was a fanlight upon which the words ‘Tyddyn Bach’ had been etched in gold lettering. The roof, covered liberally in moss and creeping yellow lichens, was of mauve-grey slate and sloped steeply, a small dormer window jutting from either side of its centre.

‘It’s a very old building, you know,’ said Mrs Parry, a touch breathlessly. ‘Older than the farmhouse itself, apparently. I’m not quite sure what its original purpose was. My father-in-law had it renovated and his old mam used to live there, after his dad passed away. We thought that Glyn and his fiancée would live there after they were married – but it just wasn’t to be …’

She stopped in her tracks and turned to look me straight in the eye. ‘You will be all right here all on your own, won’t you?’ She looked suddenly concerned.

‘I mean, being in a strange place – and you expecting and everything. A lot of folk might feel a bit uneasy with that, I know …’

I shook my head. ‘I’ve been on my own these past few months,’ I sighed. ‘I’ve never felt so alone. At least here I won’t have memories everywhere I look. And my sister will be joining me soon. No, honestly; I’ll be fine.’

‘When is baby due?’

‘Not for another three months. I’ve just started to balloon to be honest – it’s getting rather uncomfortable.’

‘I know that feeling! It’s no fun, carrying all that excess weight around. I remember my back playing up something awful!’ She smiled a little ruefully.

‘Well, you know where we are if you need anything – and you’re welcome to come over to the farm whenever you like.’

I thanked her for her kindness. She reached out with both hands and squeezed mine affectionately.

‘Oh, Mrs Parry, your hands are so cold!’ I clasped them in disbelief.

‘“Cold hands, warm heart” – isn’t that what they say?’ She laughed. ‘Poor circulation, you know, but very useful when it comes to making pastry!’

In spite of the warmth of the evening I noticed her shiver slightly. She wrapped her arms across her chest and rubbed her shoulders. ‘Old age, you know. Slows the blood. Such a nuisance.’

She hesitated momentarily, then held the door open for me. ‘Croeso! That’s how we say “welcome” up here.’

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Начислим

+9

Покупайте книги и получайте бонусы в Литрес, Читай-городе и Буквоеде.

Участвовать в бонусной программе