Книгу нельзя скачать файлом, но можно читать в нашем приложении или онлайн на сайте.

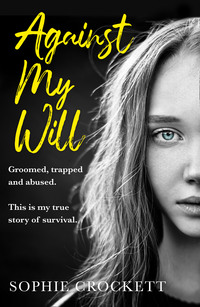

Читать книгу: «Against My Will», страница 3

Chapter 3

Blending steely determination with more than a little natural grace, I moved through the ballet moves, concentrating hard to maintain perfect posture throughout. Glissade through assemblé to relevé, I loved the combination of discipline and elegance, and the pursuit of producing something beautiful.

‘Excellent, Sophie,’ my dance teacher said. ‘You move beautifully. Well done.’

Ballet was such a revelation for me. I felt that I belonged there. The long trips to the school didn’t faze me, and for a couple of years I loved dancing. I quickly reached quite a high standard, practising hard to pass my exams and move through the grades. It seemed like no time before I was dancing en pointe, just like the ballerinas I’d so admired at the Coliseum. I was enjoying it so much that I was even looking ahead and considering going to the prestigious Northern Ballet School in Manchester to continue my development, even though it was precisely the type of leap into the unknown that would usually have had me panicking. That’s how seriously I was taking it.

That was until one day, when my teacher sat me down on the floor and said, ‘You could be such a good dancer, Sophie,’ she paused, her eyes scanning my already slender frame, ‘if you lost some weight.’

She said it so very casually, like it was just another step I had to learn. For any girl to be told that – even one without autistic traits – is dangerous. Some people might be able to brush off a comment like that and not take it seriously. Someone like me, however, prone to obsessive behaviour and with an addictive personality, immediately took it to heart.

I went home and looked at myself in the mirror. Anyone else standing beside me would have seen a thin little girl. But as I examined myself I thought, Maybe she has a point. I pulled at my stomach and examined my arms and legs. Had I got fatter? I wanted to please my teacher. If I wanted to become a proficient dancer then I had to take on board what she said.

Okay, I thought, I have to lose weight.

My confidence in my body was already shaky. I had a keen interest in fashion and at one stage dreamed of being a model, but there were parts of my body I had issues with, and wearing a leotard and tights in a room full of mirrors, you notice these things more. I admired very skinny models and ballet dancers and had in my head the quote by George Balanchine, co-founder of the New York City Ballet and one of the world’s most influential choreographers: ‘You can only dance if you can see the bones.’

My teacher was always quite intense. She was so strict she could have been straight out of a Russian ballet company. I liked her discipline, though, and I responded to the challenges she set for me. She used to be a dancer and still choreographed for a ballet company. She knew what it took to reach that standard. I wanted to be a dancer, just like her, which was why I took her very seriously when she made those comments and others about the way I looked.

I didn’t tell anyone about our conversation or how I was thinking, but in the days and weeks that followed I started to look at the food put in front of me. Suddenly it didn’t look like a wholesome, nutritious meal, lovingly prepared by my mum anymore. Instead, I imagined every morsel adding rolls of lumpy fat to my body. It was completely irrational, I know, but it seemed a perfectly sensible attitude at the time. I began calorie-counting everything, cutting out any treats and limiting myself to around 500 calories per day.

I thought I was doing well, but not long after, when I arrived for my lesson, my teacher’s eyes scanned my body again. I immediately felt self-conscious. Had I overindulged? I thought I was being good. How did she know? Was it that obvious? I went home even more determined to show her that I could lose weight – and fast.

At night I exercised in my bedroom, doing hundreds of sit-ups and press-ups. But when I checked myself again in the mirror it wasn’t enough. I just looked the same. I sat down on the floor feeling wretched. I needed to do more. I went into the bathroom, took my toothbrush and shoved it as far as it would go down my throat. I gagged at first; I wasn’t sure if I could go through with it. I pushed it further back. That did the trick. I slumped over the toilet as my stomach emptied into the pan. That was much better! I was now far more pro-active in my quest for skinniness.

At first no one noticed. You can get away with saying you’re not hungry or that you’ve ruined your appetite by eating too many snacks during the day. Quickly, though, like the other things in my life I’d become fixated on, it became an obsession.

I started picking at my food, cutting it into small pieces, making it look like I was tucking in as normal, but when no one was looking I discreetly tipped it into the bin. I’d take meals up to my bedroom when I could. Food became the enemy. I hated the idea of eating anything. I used to look at my meals, things I’d previously loved eating, and think, No, I don’t want to eat that, think what it will do to me – no way.

As I starved myself of nutrients and energy, I became lethargic and ill. That helped because the first thing to go when you feel off colour is your appetite. The weight dropped off me. I was always slender but soon I was really skinny. Still it wasn’t enough. Whenever I looked in the mirror, all I’d see was a fat girl.

I wrote notes to myself about how big I was and took a marker pen and scrawled on my stomach the word ‘Fat’. I wrote the same on my arms and legs, on any part of my body I didn’t like. If I felt hungry I looked at the words and I wouldn’t eat.

At dance class I hoped my teacher would notice the effort I was making. She did and praised me for it. One weekend, though, I lost control and ate a treat. At my next lesson she somehow knew.

I started logging on to pro-anorexia websites, where I found a raft of clever ideas – despicable, of course, for a young girl to view, but when you have an eating disorder your personality changes completely and these disturbing websites spoke to the new me. I imagined food as vomit or being maggot-infested. I brushed my teeth right before having to eat in an effort to put me off my meals. If I felt really hungry, I punched myself in the stomach – punishment for it making me feel that way.

During one mealtime my parents got suspicious and encouraged me to eat up. I kept saying, ‘I am not hungry,’ over and over. They had a go at me, telling me I was wasting away. To keep them off my back I ate everything on my plate. As soon as I was done I rushed to the bathroom and reached for my toothbrush. I started to gag and then brought my entire dinner back up. That felt good. Like I was winning.

Even though I was getting weaker and weaker, I kept pushing myself, both to do well at ballet and to get even thinner. My parents reached out to the mental-health team, which had previously supplied the psychiatrists to assess my anxiety attacks. A crisis team came to visit me at our house.

A mental-health nurse tried to offer practical solutions. ‘Why don’t you join a gym?’ she said. ‘That would help you gain confidence and reinforce positive connections with food, because it provides the energy you need to be healthy.’

It looked like she was helping, but my parents weren’t present for what else she said.

‘You know, Sophie,’ she said, when we were alone, ‘there are parts of my body I don’t like. I hate my thighs, for instance.’

She was probably just trying to help by showing that most people have insecurities over their bodies, but I looked at her and saw someone really thin already. Her words had the opposite effect. They reinforced my own attitudes.

A psychiatrist I saw told my mum and dad to follow me upstairs after a meal and sit outside the door in case I made myself sick. This didn’t help either, as it made my toilet phobia worse. And being pushed to eat just made me detest mealtimes even more, which led to huge arguments with my parents, as they were so concerned about me and didn’t know what to feed me or what to do.

The psychiatrist also advised them to remove all the mirrors from the house because every time I looked in one I saw a huge, obese creature looking back. It didn’t make much difference; even though I was getting so thin I felt constantly ill, I still thought I was fat. In my mind the weight loss wasn’t happening fast enough. Without mirrors to examine myself in, I obsessively checked myself against my clothes, and was elated when I got a size-four top and it was a little too big for me. I felt so happy then – but still it wasn’t enough. I was addicted to losing weight.

My actions seem crazy and irrational to me now, but back then I was locked into a course of action and nothing would persuade me otherwise. I ordered diet pills over the Internet without my parents knowing. At night I lay in bed stroking my hip and rib bones, feeling pleasure that I was achieving something.

My health rapidly deteriorated further. I felt dizzy and struggled to concentrate on anything for any length of time. My schoolwork suffered. As I entered my teenage years I didn’t much rate my tutors anyway. After the episode with Mary, the local authority sent me primary-school teachers who again taught me according to my age rather than ability, and I felt stifled and uninspired. It didn’t help that I continued to starve myself and immediately ran to the bathroom to throw up if I did eat a meal. If I had to go outside, I carried a toothbrush in my bag in case I needed to stick it down my throat to bring up anything I’d eaten.

My parents were at their wits’ end – first the anxiety, then the overly attentive tutor and now this. An eating disorder, the kind of thing they’d only read about or watched on television. Yet here it was, happening to their daughter, and they felt powerless to stop it and even less able to understand it.

They took me to the doctor. He saw I was in the grip of anorexia nervosa and bulimia, but also said I was clinically depressed – bipolar, in fact – capable of experiencing highs but also devastating lows. He suggested putting me on medication. No way! Ever since I was a young child I’d had a phobia about taking drugs. There was no way I was putting pills down my throat.

He was right, though – I was depressed. I was sinking deeper and deeper into a black hole of my own making, because my addictive personality had latched on to my teacher’s negative attitude to food. Still, I didn’t let on to my parents or the health professionals about the root cause of my behaviour, and so we kept going to ballet.

Yet rather than praise me for my dedication, my dance teacher turned on me. One day I couldn’t get on my pointes enough – probably due to a lack of energy because I was so skinny. She grabbed me by the hips and shoulders and shook me. I came home feeling broken, my body covered in bruises.

Ballet was no longer fun. It had been the only source of joy in my life, but it had turned sour. I sank lower. I hated ballet, I hated my teacher, but worst of all I hated myself. I hated the fact that I was the way I was. I hated being condemned to forever living as a prisoner to my condition. I wasn’t in control; I was at the mercy of the Asperger’s that ruled my mind. I hated my life. I felt cursed. If I was in tune with the spirit world, it wasn’t able to help me. Medication wasn’t the answer. I needed to find something else to relieve the pain in my head, to ease the blockage of self-loathing.

I felt an overwhelming need for release. Instinctively, I went to the bathroom and saw one of my dad’s Bic razors. I pushed it against my leg – to my eyes the fleshiest part of my thigh, even though it was stick thin. I pushed the blade deeper into my leg, watched as it broke the skin. It felt good. It was exactly what I needed.

As the blood oozed from the perfect cut it was like a valve had been opened, and all the tension was seeping out of me. It was amazing. I had never heard of self-harming. I wasn’t even aware it was a concept. I just knew I’d found something that eased my pain.

But, like my quest to be as thin as possible, my desire to cut myself became an obsession. I gouged my skin at every opportunity. Every time I cut myself I told myself I deserved it. It wasn’t like punishment, though. This was so, so sweet. I could breathe again.

I had a compulsion. Every time I got stressed I’d reach for the razor blade. It got to the point where I carried a razor blade in my handbag just in case. I always made the cuts on my leg because I could cover them up. I certainly wasn’t doing this for attention. That was the last thing I wanted. I never showed anybody my scars. I was ashamed of them. I didn’t want anyone to know what I was doing.

Once I got into it, I did quite a lot of damage. I got carried away, slicing and searching for patches of virgin skin. I was a mess, physically and mentally.

I turned to poetry, penning my own verse to try to put my pain into words. One poem from that time was called ‘Maze of the Mind’.

Distorted image that was once so true.

Failure to recognise oneself.

Loathing of this shell I carry.

Losing my inner self.

Which image is honest?

Which image is truth?

Am I not as real as you?

My mind is a maze of twists and turns.

That no longer has substance.

A nothingness has sucked life dry.

A blackness has engulfed me.

Mental suffocation but physically well.

Screaming in frustration yet sitting calm and still.

‘How are you?’ they say.

‘I’m well,’ I reply.

But I feel already dead.

Being in such a distraught state presented the perfect opportunity for a predator to pounce. My psychic senses might have been clouded to any potential danger, but someone else claiming to have spiritual powers spied an opportunity to prey on an impressionable victim.

Chapter 4

It looked harmless enough. Fun, even. And I hadn’t exactly enjoyed many fun times before we paid a trip to Brecon. I was with my parents and sister, and my primary reason for going there was to visit a bookshop. On the opposite side of the street was a spiritual crystal shop hosting a fair for all kinds of psychic practices. My kind of place, surely?

Once we went inside I saw that a psychic artist, who I will call Phil, was offering readings through art.

‘I’d like to get this,’ I said.

My parents shrugged and said it was fine, if that was what I wanted. Phil seemed perfectly nice and showed me upstairs to a small room where he did his artwork, while my family waited downstairs. He talked quietly and asked me some questions to get a sense of who I was so he could tune in and contact my spirit guide. He asked for some personal information, my name and phone number. I gave these to him without thinking much of it. Phil then explained that he would tune in to my spirit and channel it through his artwork.

I sat there, quite intrigued. He was sketching the figure of a man, but with large wings. As he was drawing he edged closer and closer towards me. I felt uncomfortable so I got up. He stood up too and I backed against the wall. He moved right in front of me, his large frame blocking the stairs. I started to feel scared. He was so close I could feel his breath on my face. He put his hand against the wall next to my head.

‘You’re a very special girl, Sophie,’ he said, pinning me against the wall.

I didn’t know what was going on. But I knew this wasn’t right. Before he could do or say anything else, I slipped under his arm and ran down the stairs. My parents were still there, waiting for me.

‘What’s wrong?’ my dad said, seeing the look on my face.

‘I don’t know,’ I said, truthfully. I really didn’t know what had just happened.

I looked back up the stairs and Phil was there holding the drawing. ‘Sophie, you forgot your picture,’ he said.

He came down casually behind me, smiling as if nothing had happened. He chatted to my dad a little bit about mundane things and said everything went well. All the time I just wanted to get away.

On the journey home my parents could sense something was wrong. They kept asking me what, but I just replied, ‘I don’t know.’

Back at the house I looked at his half-drawn picture to see what meaning I could glean from it. Not much. A short while later my phone buzzed with a message. It was Phil. He asked how I was and said he was sorry I ran off. Why was he contacting me? He knew I was only 14, but I looked much younger. I was confused. My brain couldn’t work out whether it was normal for a middle-aged man to contact a young teenage girl. Shut away in my house, with none of the interactions with boys that other girls my age might get at school and parties, I was completely naïve.

It didn’t feel right, but I didn’t know what to do. I texted him back: ‘I’m fine.’

The texts kept coming. He said he liked me, that he was sorry he hadn’t been able to finish his sketch. He said he was only trying to help me. He had seen something special in me and wanted to help me understand more about what it meant.

I suppose I was flattered that this older man was paying attention to me. But it made me uncomfortable. This couldn’t be how normal people behaved, could it? What was normal anyway?

I was still in the grip of my eating disorders and depression, so to become withdrawn and quiet wasn’t new, but still my parents sensed something else was going on. They asked me repeatedly what was up, but I said nothing. I was too scared to tell them about what had happened upstairs at the spiritual fair or the texts. Maybe they would blame me. Maybe I was doing something wrong.

The texts became more frequent and the tone changed. Phil was clearly fascinated by me.

‘Can you send me some photos of you,’ he said in one text.

I didn’t want to. He started pressurising me. I sent him one photo but he came back immediately. That wasn’t what he wanted. He wanted something much more explicit – a photo of me in my underwear.

I was completely innocent. Not being at school meant I had missed out on sex education. In the books I’d read the sexual element was implied rather than explicitly detailed. I was very young in the head with regards to sexual relations, but it still felt wrong. I felt I had to do what he said, though. When I didn’t respond he called me. He spoke so confidently and smoothly, as if this was the most normal thing in the world and it was me who was being weird and difficult by not sending him what he wanted.

It felt wrong and strange to do it, but I took a photo of myself in my underwear. Why would anyone want that? I didn’t want to send it to him, but I felt like I had to because he was putting me under so much pressure. Reluctantly, I sent it. If I’d thought that was going to satisfy him, I was wrong. It only escalated further. He quickly demanded more pictures, even more explicit ones.

Next, he phoned me. ‘Guess what I’m doing right this moment,’ he said. I had no idea. I couldn’t even begin to imagine.

The idea of relationships was confusing for me. I had a skewed idea of what one should be like because my brain is wired in a very strange way. I just don’t know what is normal and what is not. I felt I had no option but to keep sending provocative photographs over text to him.

This type of correspondence went on for quite a while. I kept it secret, though. I wasn’t sure what would happen if I told anyone. Then one day he phoned me: ‘I’m coming to Brecon. I want you to meet me.’

Now I was scared. I had felt almost detached from it before, conducting things over the phone, but meeting up would suddenly make it real. Brecon was 30 miles away, so it would take some effort for me to get there.

‘Come and meet me,’ he persisted. ‘I’ll get the bed ready.’

That was it. It hit me in the face then. I can’t do that, I thought. I was scared. I still didn’t know what to do. All I knew was that I wanted it all to stop. I couldn’t think of what else to do, so I threw my phone in the bin. My parents thought it strange that I had lost my phone, but I refused to let them in on the real story. I was quite shaken by the whole experience, and it made me question his motives. Was he really a genuine psychic or was it all a sham? I suspect it was the latter.

The episode with Phil came at a terrible time, when I was full of self-loathing and wasting away physically. I was starving myself. My health really deteriorated. I had little-to-no energy, but I would still push myself to exercise for hours at a time. My hair started falling out and my nails stopped growing. My periods became very irregular and eventually stopped altogether. I started getting spots and my hair was always greasy. At my lowest points, as well as cutting myself, I’d pull out clumps of hair.

Despite my physical and mental torment, I felt like I was achieving. I felt in control, like I was doing what I was supposed to do. It might sound strange, but I felt happiness at the suffering and pain, because I thought, You can’t get what you want or be happy unless you go through pain.

For my mum and dad it was torture. They just couldn’t understand why I would do this to myself. They continued to take me to see my psychiatrist. He kept pushing me to take antidepressants. I confided in him about my need to self-harm. He took out a toy doll and said, ‘Pull the hair out of this.’

I looked at him like he was mad. How was that the same as pulling your own hair out?

‘Put tomato ketchup on your legs,’ he said, in response to the scars I was making. How could I compare the two? Self-harming was a pain I was willing to endure to take my mind off other things. The idea of putting ketchup on my leg just sounded strange. I just thought about how sticky I’d get, which repulsed me.

I was developing obsessive-compulsive disorder, and had started to value cleanliness above nearly everything else. The thought of willingly smearing ketchup on my legs was a no-no. Among my many daily rituals was obsessive hand-washing. I washed them over and over in the hottest water to kill the germs, until my hands were red. I had other rituals too, like doing specific hand movements a certain number of times. I’d turn around a certain number of times too, because I believed that if I didn’t do it something bad would happen. I lay awake half the night doing hand gestures over and over again, because if I didn’t do them 300 times I was certain something really bad was going to happen. There had been nothing to spark this. It was just something I had convinced myself of.

My OCD feels like something that has always been there. I can’t remember how or when it started. I just always had to do things. In the 1990s the condition, like Asperger’s, wasn’t that understood. In rural Wales there just wasn’t the health-care provision to advise on it.

In the grip of this mental maelstrom, my weight plummeted. I was down to six stone. My clothes hung off my skeletal shoulders. It became deadly serious then. The psychiatrist was clear about what action was needed.

‘Sophie, you have a stark choice to make,’ he told me. ‘You can either stop dancing and go on antidepressants, or go to a psychiatric hospital where they will look after you.’

The thought of going to hospital terrified me. It was no choice, really. Reluctantly, I agreed to the medication. He prescribed the antidepressant fluoxetine, known more commonly as Prozac, for my desperately low mood, and diazepam, or Valium, for the anxiety. Despite my age, they prescribed a high dosage because my situation was so serious. We were at the point where they needed to do something or there was a risk I could do something really stupid.

The medication had an immediate effect. My mood lifted and I felt less inclined to cut myself, and with the edge taken off my anxiety, everyday things seemed less stressful. For the first time I thought I could go out, and that was a big deal. I went to the pharmacy by myself and, although it sounds like such a small thing, to someone who had effectively been locked inside all her life it was massive. It was like climbing Mount Everest.

As I’d done before when I’d been feeling depressed, I tried to articulate my feelings in poetry. One from that time was called ‘My Time Is Now’.

My time for living is now.

I will no longer sleep,

As I have awakened from my long-lasting slumber.

It is too late to turn back.

The gate has closed.

My path is fixed.

Now out into the world I go!

With a smile on my face and love in my heart.

From my love I must depart.

Save your tears.

Do not cry.

Look into your memories for comfort from me.

Do not weep for you see I am already gone.

It was still a struggle, as those words demonstrate, but slowly I was engaging with the world around me. I could walk in the park near my house, go down into the town centre. By this point I was 16 and only beginning to sample things that everyone else took for granted.

The more my mood lifted, the more I wanted to meet people, so I looked to see if there were groups I could join. After years locked in my private universe, I was venturing out into the real world. What I didn’t know was that evil was waiting.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Начислим

+20

Покупайте книги и получайте бонусы в Литрес, Читай-городе и Буквоеде.

Участвовать в бонусной программе