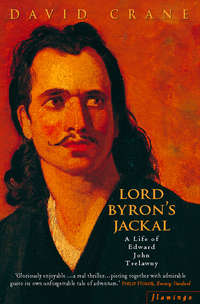

Читать книгу: «Lord Byron’s Jackal: A Life of Trelawny», страница 3

Shortly after coming under De Ruyter’s spell, the incident occurred in this imaginary version of events that ended Trelawny’s naval servitude. The two men were playing billiards, when a Scotch lieutenant who had tormented his and Walter’s lives entered. He demanded to know when Trelawny was rejoining his ship, which was sailing the next day. At this Trelawny’s blood seemed to ignite with fire, and then congeal to ice. He dashed his hat in the man’s face, tore off the last insignia of bondage from his own dress, and drew his sword. The lieutenant broke into abject disclaimers of friendship, and begged his pardon. In his rage Trelawny struck him to the ground, kicking and trampling and spitting on him as the creature begged for mercy. ‘His screams and protestations,’ Trelawny wrote,

while they increased my contempt, added fuel to my anger, for I was furious that such a pitiful wretch should have lorded it over me so long. I roared out, ‘For the wrongs you have done me, I am satisfied. Yet nothing but your currish blood can atone for your atrocities to Walter!’

Having broken my own sword at the onset, I drew his from beneath his prostrate carcass, and should inevitably have despatched him on the spot, had not a stronger hand gripped hold of my arm. It was De Ruyter’s; and he said, in a low, quiet voice, ‘Come, no killing. Here!’ (giving me a broken billiard cue) ‘a stick is a fitter weapon to chastise a coward with. Don’t rust good steel.’

It was useless to gainsay him, for he had taken the sword out of my hand. I therefor belaboured the rascal: his yells were dreadful; he was wild with terror, and looked like a maniac. I never ceased till I had broken the butt-end of the cue over him, and till he was motionless.23

The young rebel who had suffered under his father’s brutality, under the cruelty of the Reverend Seyer, and in the navy, was at last free. The mysterious De Ruyter who had passed himself off in Bombay as a merchant, now revealed himself as a privateer operating under a French flag, an enemy to all tyranny and corruption, and in the seventeen-year-old midshipman recognized his spiritual heir and child.

It was the beginning of a new life, and under the leadership of this man, Trelawny embarked on the imaginary career of adventure, excitement, bloodshed, romance and crime which forms the great bulk of his ‘autobiography’. There is no summary of Adventures that can possibly do justice to the colour and imaginative profligacy of his fantasies, nothing that can capture either the compelling immediacy of Trelawny’s fictional world or the visions of violence and domination with which he took his revenge on Caroline and a world that stolidly refused to come up to expectations. As a lonely and unhappy young midshipman, he had daydreamed with his friend Walter of a life without parents, patrimonies or ties ‘amidst the children of nature,’24 but the dreams now were more sinister. Crazed stallions, Malay peasants, naval officers, ugly old women are all brutally mastered, bullied, beaten, burned, killed or crushed like toads beneath his feet. The vegetation and landscape of the east which so prosaically reminded Lord Minto of a Chinese wallpaper, takes on a vivid almost surrealistic life. Wild animals fill his vision with the same haunting, threatening force that they have in Othello. It is wish fulfilment on the grand scale. In De Ruyter the emotional orphan has found a father; in the lovely Zela, shy and beautiful as a faun, devoted to Trelawny until she expires in his arms after a shark attack, the cuckold at last finds the bride he deserves; and in the excitement, colour and violence of his adventures, the unemployed midshipman wins the recognition the Royal Navy had denied him.

After the public humiliations of the King’s Bench and Consistory Courts, Trelawny was ready to face the world, a Byronic hero with a history and personality to match. In the depths of his imagination he had forged an identity which seemed more vividly true to his sense of self than the reality he had left behind, and if the same might be said of every creative liar, what distinguishes him from a Savage or Baron Corvo is that for the next five years life was to give him what he wanted with an almost Faustian prodigality – years in which invention became a self-fulfilling ordinance, and events danced to the tune of the imagination until fantasy and life pursued each other in an unbreakable circle.

If psychologically he was prepared for a new life, financially, too, he was at last able to expand his horizons. Through all the rows with his father he had continued to draw an allowance of three hundred pounds a year, and while that was scarcely enough to support a family in comfort, for a single man ready to live abroad it opened up possibilities of leisured and gentlemanly self-indulgence. On 19 May 1819, the Royal Assent to his divorce was given, freeing him of those domestic ties which had shackled his turbulent spirit. The seven lean years were over. Caroline, at last, was out of his life, taking their younger daughter, Eliza, with her. The elder child, Julia, had been farmed out to friends of the Whites. He seems to have backtracked too from the brief intensity of his friendship with Augusta, allowing it to mellow into a mutual warmth which lasted throughout their lives.

The disappointment and failures of the navy and marriage, the first-floor parlours and bedrooms, were not just forgotten but buried. Mentally he had toughened and changed, developing out of all recognition from the dull lout his uncle had found him ten years earlier. At the age of twenty-eight he had also physically grown into the role he had created for himself, tall, dark, athletic, immensely strong and handsome. All he needed now was a stage on which to play out his new part. His father had offered to buy him a commission in the army, but for a follower of De Ruyter that was hardly an option. He had talked vaguely for a time of South America as well, of joining either General Wilson or a commune. In the end, however, he settled for the Continent. One of his last addresses in England before leaving was 7 Orange St, the site now of the archives of the National Portrait Gallery. It was a prescient choice of address for a man about to launch himself into the forefront of the nation’s consciousness.

2 THE SUN AND THE GLOW-WORM

‘You won’t like him.’

Byron to Teresa Guiccioli 1

IT MUST HAVE BEEN sometime in the autumn of 1819 or the beginning of 1820 that Trelawny finally left England for the Continent, travelling first to Paris where his mother was chaperoning his sisters on a predatory hunt for husbands, and from there to Geneva.

With the poverty of letters from this time it is impossible to be dogmatic about Trelawny’s motives but there would have been compelling reasons other than disappointment and money for his decision to live abroad. There appears to have been nothing particular in his choice of Switzerland, but for a man of his burgeoning radicalism the England of Castlereagh and the Peterloo Massacre can have seemed no place to be, a country frozen in the mini ice-age of reaction which gripped post-Napoleonic Europe, a land, in Shelley’s savage assault, of,

An old, mad, blind, despised, and dying king, –

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through public scorn, – mud from a muddy spring, –

Rulers who neither see, nor feel, nor know,

But leech-like to their feinting country cling,

Till they drop, blind in blood, without a blow, –2

At a time when so many European liberals were seeking refuge in England, there seems something stubbornly wrongheaded in the reverse process, but for Trelawny at least the freedom the Continent offered had more to do with the texture of life than any considered set of principles. Like so many men of his nation and class nineteenth-century Europe represented above all else a continuation of the eighteenth century ‘by other means’, an opportunity – heterosexual, homosexual, financial, social or whatever – to pursue a style of life which inflation and the looming threat of ‘Victorian’ morality was endangering at home.

It was an opportunity he embraced with relief and gusto, but amidst the shooting, hunting and fishing that signalled a reabsorption into his own class, a meeting occurred that was to change the direction of his life for good. A family friend of the Trelawnys from the West Country, Sir John Aubyn, kept a generous if irregular open house at his villa just outside Geneva, and it was in this motley expatriate world that Trelawny first met Edward Williams, an Indian army officer living in Switzerland as a married man with the wife of a fellow officer, and Thomas Medwin, the cousin of Percy Bysshe Shelley.

The friendship of Williams, at least, was one that Trelawny treasured all his life, but more important, it was through these two men that he now found himself drawn into the Italian orbit of Byron and Shelley. There is no way of being sure when he first came across the name or work of a poet who, in 1820, was known mainly for his atheism, but Trelawny’s account invests the occasion with a significance that is poetically if not literally true. The scene is set in Lausanne in 1820, during a conversation with a bookseller-friend, who would translate passages of Schiller, Kant or Goethe for an ex-midshipman still painfully conscious of his lack of education. The story forms the opening scene of his Records of Shelley, Byron, and the Author and among the apocrypha of his early life it holds a special place.

One morning I saw my friend sitting under the acacias on the terrace in front of the house in which Gibbon had lived, and where he wrote the Decline and Fall. He said, ‘I am trying to sharpen my wits in this pungent air which gave such a keen edge to the great historian, so that I may fathom this book. Your modern poets, Byron, Scott, and Moore, I can read and understand as I walk along, but I have got hold of a book by one that makes me stop to take breath and think.’ It was Shelley’s ‘Queen Mab’. As I had never heard that name or title, I asked how he got the volume. ‘With a lot of new books in English, which I took in exchange for old French ones. Not knowing the names of the authors, I might not have looked into them, had not a pampered, prying priest smelt this one in my lumber-room, and after a brief glance at the notes, exploded in wrath, shouting out, ‘Infidel, jacobin, leveller: nothing can stop this spread of blasphemy but the stake and the faggot; the world is retrograding into accursed heathenism and universal anarchy!’ When the priest had departed, I took up the small book he had thrown down, saying, ‘Surely there must be something here worth tasting.’ You know the proverb, ‘No person throws a stone at a tree that does not bear fruit.’

‘Priests do not’, I answered; ‘so I, too, must have a bite of the forbidden fruit.’3*

Set alongside the impact of Byron on Trelawny, the influence of Shelley’s poetry seems virtually negligible, but this, in stylized form, is still one of the key moments of his life. A few days after this exchange he was breakfasting at a hotel in Lausanne, when a chance conversation with an Englishman on a walking holiday with two women gave him his first opportunity to test this new enthusiasm. It was only after their party had broken up that Trelawny learned that the ‘self-confident and dogmatic’ stranger was Wordsworth, but chasing him down again he ‘asked him abruptly what he thought of Shelley as a poet.

‘Nothing,’ he replied, as abruptly.

‘Seeing my surprise, he added, ‘A poet who has not produced a good poem before he is twenty five, we may conclude cannot, and never will do so.’

‘The Cenci!’ I said eagerly.

‘Won’t do,’ he replied, shaking his head, as he got into the carriage: a rough-coated Scotch terrier followed him.

‘This hairy fellow is our flea-trap,’ he shouted out as they started off …

I did not then know that the full-fledged author never reads the writings of his contemporaries, except to cut them up in a review – that being a work of love. In after years, Shelley being dead, Wordsworth confessed this fact; he was then induced to read some of Shelley’s poems, and admitted that Shelley was the greatest master of harmonious verse in our modern literature.4

It says a lot for Trelawny’s critical judgement that, almost alone and untaught, he could have discovered Shelley for himself, but there must also have been more personal and less literary factors that helped quicken his new interest. For a man who saw himself in the self-dramatizing terms he so habitually used, the exiled poet would have offered a mirror to his own miserable experience, and if Shelley was merely the ‘glow-worm’ to Byron’s ‘sun’, then that can only have made him appear more accessible. The arrival of Medwin meant too that the chance of meeting him was something that had probably been discussed from the earliest days in Switzerland, but the unlamented death of Trelawny’s father in 1820 put any thoughts of Italy back by at least a year. Travelling in his own carriage through Chalon-sur-Saône, where he left Edward and Jane Williams to winter in genteel poverty, he continued on to England with his financial hopes high only to discover that he was no better off than he had been before. The old uncertainty of the allowance, the galling necessity of tempering hatred with self-interest, was gone, but there was to be no more money. He had been left £10,000 in 3% gilt-edged stocks which gave him an income of £300 a year.

The evidence for Trelawny’s movements during these months is as sketchy as for any time of his life, but it is likely that arriving in England at the end of 1820 he found himself in no hurry to leave, staying at his mother’s new London home in Berners Street before returning to the Continent in the May or June of 1821.

It is at this moment as one begins to attempt to chart his steps, however, that it becomes obvious just how futile an exercise it is, and just how far at this point a traditional sense of ‘biographical’ time must give way to what could be called ‘Trelawny’ time. Because to any observer totting up the weeks and months spent shooting and hunting during these years a picture emerges of a life hopelessly and terminally adrift, and yet for Trelawny himself this same time seems to have been crushed into a series of defining highlights that obliterate all else, secular epiphanies which, in the great drama he made of his life, assert a pattern of significance – of destiny – that biography can do nothing but follow.

Throughout his life there would be an almost Marvellian fierceness in the way Trelawny would seize his opportunities and in 1820 this destiny seemed to him to lead nowhere but Italy. Through the summer of 1821 he hunted and fished with an old naval friend Daniel Roberts in the Swiss mountains, but beneath the seemingly aimless wanderings the real business of his life was already taking shape. In April 1821, Edward Williams had written to him from Pisa, where he and Jane were living after a bleak winter of ‘soupe maigre, bouilli, sour wine, and solitary confinement’ at Chalon-sur-Saône.5 He was, he told Trelawny, already an intimate of Shelley. They were planning a summer’s boating together, ‘adventuring’ among the rivers and canals of that part of Italy. ‘Shelley’, he wrote, tantalizingly

is certainly a man of most astonishing genius in appearance, extraordinarily young, of manners mild and amiable, but withal frill of life and fun. His wonderful command of language, and the ease with which he speaks on what are generally considered abstruse subjects, are striking; in short, his ordinary conversation is akin to poetry, for he sees things in the most singular and pleasing lights; if he wrote as he talked, he would be popular enough. Lord Byron and others think him by far the most imaginative poet of the day. The style of his lordship’s letters to him is quite that of a pupil, such as asking his opinion, and demanding his advice on certain points, &. I must tell you, that the idea of the tragedy of ‘Manfred’, and many of the philosophical, or rather metaphysical, notions interwoven in the composition of the fourth Canto of ‘Childe Harold’, are of his suggestion; but this, of course, is between ourselves.6

Trelawny printed this letter in his history of this period of his life, the Records of Shelley, Byron and the Author. Back to back with it, as if the intervening eight months had simply not existed, comes a second letter from Williams, written in the following December and giving the momentous news of Byron’s arrival.

My Dear Trelawny,

Why, how is this? I will swear that yesterday was Christmas Day, for I celebrated it at a splendid feast given by Lord Byron to what I call his Pistol Club – i.e. to Shelley, Medwin, a Mr Taaffe, and myself, and was scarcely awake from the vision of it when your letter was put into my hands, dated 1st of January, 1822. Time flies fast enough, but you, in the rapidity of your motions, contrive to outwing the old fellow … Lord Byron is the very spirit of the place – that is, to those few to whom, like Mohannah, he has lifted his veil. When you asked me in your last letter if it was probable to become at all intimate with him, I replied in a manner which I considered it most prudent to do, from motives which are best explained when I see you. Now, however, I know him a great deal better, and I think I may safely say that point will rest entirely with yourself. The eccentricities of an assumed character, which a total retirement from the world almost rendered a natural one, are daily wearing off. He sees none of the numerous English who are here, excepting those I have named. And of this I am selfishly glad, for one sees nothing of a man in mixed societies. It is difficult to move him, he says, when he is once fixed, but he seems bent upon joining our party at Spezzia next summer.

I shall reserve all that I have to say about the boat until we meet at the select committee, which is intended to be held on that subject when you arrive here. Have a boat we must, and if we can get Roberts to build her, so much the better … 7

With the entry of Byron into Shelley’s world Trelawny’s twin deities were in place. Even before Williams’s second letter, however, he was already making ready for Italy. He had shipped his guns and dogs to Leghorn in preparation for a winter’s hunting in the Maremma, but with this news of bigger game on the banks of the Arno, the woodcock were now going to have to wait their turn.

Travelling south from Geneva with his friend Roberts, shooting, fishing and sketching as they went, Trelawny finally reached Pisa in the January of 1822 to take up his place among the circle that had formed around Shelley. Since the early spring of 1818 when they left England for the last time, Shelley and his tribe of dependents had been wandering across the Continent, moving restlessly from one Italian town to another, from Milan to Bagni di Lucca, Venice, Naples, Rome, Leghorn, Florence, and then, in the January of 1820, to Pisa, his penultimate resting place in that ‘Paradise of exiles – the retreat of Pariahs’ as he called nineteenth-century Italy.8

At the beginning of 1822, when Trelawny first joined them, Shelley and his wife Mary were living above Edward and Jane Williams in the Tre Palazzi di Chiesa at the eastern end of the Lung’ Arno, diagonally across the river from the Palazzo Lanfranchi which Byron had taken the previous November. Anxious to be with them as quickly as he could, Trelawny had left Roberts at Genoa and hurried on alone. He arrived late, and after putting up his horse at an inn and dining, hastened to the Tre Palazzi to renew acquaintances with the Williamses and to meet Shelley. He was greeted by his old friends in ‘their earnest cordial manner’, and the three were deep in conversation,

when I was rather put out by observing in the passage near the open door, opposite to where I sat, a pair of glittering eyes steadily fixed on mine; it was too dark to make out whom they belonged to. With the acuteness of a woman, Mrs Williams’s eyes followed the direction of mine, and going to the doorway, she laughingly said.

‘Come in, Shelley, it’s only our friend Tre just arrived.’

Swiftly gliding in, blushing like a girl, a tall thin stripling held out both his hands; and although I could hardly believe as I looked at his flushed, feminine, and artless face that it could be the Poet, I returned his warm pressure. After the ordinary greetings he sat down and listened. I was silent from astonishment: was it possible this mild-looking beardless boy could be the veritable monster at war with all the world? – excommunicated by the Fathers of the Church, deprived of his civil rights by the fiat of a grim Lord Chancellor, discarded by every member of his family, and denounced by the rival sages of our literature as the founder of a Satanic school? I could not believe it; it must be a hoax.9

This account was published in his Records almost sixty years after, at a time when Trelawny was established beyond challenge as the last and greatest of Byron’s and Shelley’s friends, and yet even if much of its ease is of a later date, he clearly slid into the world that revolved around the two poets as if he had known no other. Within twenty-four hours of this first sight of Shelley he was playing billiards with Byron at the Palazzo Lanfranchi, coolly holding his own in conversation (and there is no more conversationally demanding a game than billiards), the acolyte an immediate familiar, a welcome addition to the daily shooting parties and drama plans and as interesting an object to his new friends as they were to him.

Indeed, when Trelawny first burst upon Byron’s Pisan world that January, launching himself from nowhere with the same fanfare of lies that fill his Adventures, it seemed to them that here at last was the Byronic hero made flesh. Here was a Conrad with a Gulnare in every port, a Lara who had exhausted all human emotion, who had murdered and pillaged, whored and sinned; had loved only to cremate his Zela’s corpse on the edge of a Javan bay; betrayed and been betrayed, deserted from the Royal Navy, fought beside his pirate-hero De Ruyter, and all, as Mary Shelley noted with that fine lack of irony that is her hallmark, ‘between the age of thirteen and twenty.’10

Appropriately, in fact, it is to the author of Frankenstein that we owe the first sustained description of Trelawny that we have. The arrival of this exotic figure among their small circle was important enough to warrant a long entry in her journal, and a month later she was still sufficiently intrigued to write to an old friend, Mary Gisborne, of her giovane stravagante. He was, she said

a kind of half Arab Englishman – whose life has been as changeful as that of Anastasius & who recounts the adventures of his youth as eloquently and well as the imagined Greek – he is clever – for his moral qualities I am yet in the dark – he is a strange web which I am endeavouring to unravel – I would fain learn if generosity is united to impetuousness – Nobility of spirit to his assumption of singularity & independence – he is six feet high – raven black hair which curls thickly & shortly like a More – dark, grey – expressive eyes – overhanging brows, upturned lips & a smile which expresses good nature & kindheartedness – his shoulders are high like an Orientalist – his voice is monotonous yet emphatic & his language as he relates the events of his life energetic & simple – whether the tale be one of blood & horror or irresistable comedy. His company is delightful for he excites me to think and if any evil shade the intercourse that time will tell.11

It seems fitting in a sense that we have no painting or description of Trelawny before this time, that we have to wait until he was the ‘finished article’ strutting the public stage to know in any detail what he might have looked like. There are moments when one feels that some glimpse of a younger and more vulnerable Trelawny might help ‘explain’ him in some way, but there is no image which even half suggests the ghost of another self – either of the boy who cried himself to sleep that first night at school, or the man who sat through Sarah Prout’s testimony in the divorce courts. By 1822, cuckold and boy were both gone, hidden behind the mask that so intrigued Mary Shelley, that stares out still from portrait after portrait done over the next fifty years – the eyes aggressive, challenging, the nose aquiline, the lines already set into the obdurate mould Millais caught in old age: the face, as Mary Shelley suggests, of Thomas Hope’s Anastasius, the one romantic outcast that Byron wept that he had not himself created.

It has always been baffling that Trelawny could have got away with his tales and fantasies among the Pisan Circle, but at a more mundane level it is scarcely less astonishing to find the daughter of Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft still thinking and writing of an uneducated midshipman in these terms after almost a month of his company.

But if charm, singularity and good-looks were possibly enough to provoke her fascination with him, something more than a lazy and tolerant male camaraderie is needed to explain away the confidence with which he adjusted to the sophisticated literary and political interests of Byron and Shelley.

The admirers of the two poets have traditionally agreed on very little but if there is one thing that does unite them it is a comforting belief that Trelawny was only a marginal figure in their Pisan Circle. The principal reason for this is a natural and proper reaction to the inflated claims he made for himself in his later memoirs, and yet even when one has discounted his exaggerations it is still clear that there was a genuine warmth in their welcome that reflects as well on him as it does on them.

There was a kindness about Shelley and an aristocratic carelessness about Byron which must have smoothed any awkwardness, but in such a circle Trelawny would have had to earn his place with his conversation or simply disappear. In old age the force and vitality of his talk left an indelible impression on all who met him, and even at thirty he was obviously a brilliant and charismatic story-teller with the power to interest men whose lives in many ways had been more circumscribed than his own.

Trelawny’s strength and skills, his shooting, his boxing and sailing were all valued currencies in Byron’s world and yet the explanation of his success that often goes forgotten is the simple fact that he was a man of real if unformed talent. In terms of sophistication and learning he might well have been out of his depth in this alien literary world, but if one takes out Byron and Shelley and that strange fluke of a novel, Frankenstein, was there anything produced by the Pisan Circle that could remotely compare with the books Trelawny would go on to write?

Williams, Medwin, Taafe, Mrs. Mason, Claire Clairmont, even Leigh Hunt? – the truth is that Trelawny wrote at least one book and probably two that were beyond the compass of any of them. There is certainly nothing in his letters from this period to suggest he had yet found the voice to match his abilities, but there must have been an inner conviction of power that rubbed off on others, a strong and even savage faith in his own singularity that enabled him to brazen out his adopted role in a world whose very lifeblood was the imagination. It is again as if all those years of misery that seem so arid and sterile from the outside had been nothing of the sort, but rather an essential apprenticeship in romantic alienation, a training in disaffection whilst the inner man, fed on little more than the poetry of Byron and Shelley, shaped for himself a destiny he was ready to seize the moment it was offered him.

Not even Trelawny, though, in the drawn-out loneliness of his life at sea or the humiliations of the divorce courts, could have anticipated that destiny would bring him to Italy in time to play his part in English Romanticism’s Götterdämmerung. Neither, during his first weeks, was there any hint of the dramas that lay ahead. Through the early months of 1822, the sexual and political tensions that were always part of their Pisan world were stirring ominously beneath the surface, and yet in the very ordinariness of Edward Williams’s journal for this same time one glimpses in its last, leisurely days a world that feels as if it might have gone on for ever.

At the end of March their peace was threatened by an unpleasant and absurdly inflated incident with a sergeant major called Masi, a degrading brawl that ended in Masi’s wounding and ultimately Byron’s exit from Pisa. Some of the details of this incident are still obscure but it began when the party of Byron and Shelley, returning from shooting practice, took umbrage at a dragoon who galloped through their ranks on the road into Pisa. When the English gave chase there was a scuffle beneath the city gate that left Shelley on the ground and a Captain Hay wounded, but it was only when an unknown member of Byron’s household subsequently stabbed Masi outside the Palazzo Lanfranchi that the incident threatened serious consequences.

After one fraught night through which he was not expected to live, Masi recovered from his wound. But anti-English feeling ran high in the city, and even before the Gambas, the family of Byron’s mistress Teresa Guiccioli, were expelled and Byron went with them, Shelley and Mary had determined to quit Pisa.

The final calamity, when it came, however, sprang from a different direction with all the suddenness and violence of the Mediterranean storm that caused it. From long before Trelawny’s appearance there had been excited talk in Shelley’s circle of boats and boating expeditions, and when Trelawny arrived in January 1822 he immediately assumed, as the ex-naval man among them, a leading role in their schemes. In his journal for 15 January, Williams noted that Trelawny had brought them a model for an American schooner, and that they had settled to have a 30-foot boat built along its lines. Within days an order was placed through Daniel Roberts for this boat, together with a larger vessel that Trelawny was to skipper himself for Byron. Then, on 5 February, Trelawny wrote to Roberts again with his last, fateful instructions, dangerously reducing the original specifications for Shelley’s boat by almost half.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Начислим

+6

Покупайте книги и получайте бонусы в Литрес, Читай-городе и Буквоеде.

Участвовать в бонусной программе